How Humiliation Drove Modern Chinese History

The British destruction of Beijing's Summer Palace in the 19th century encapsulates how the emotion played a major role in forming modern China.

In June 1840, following the breakdown in negotiations with the Qing Dynasty over the trade of opium on Chinese territory, a large British military force captured the city of Canton (now Guangzhou) before marching up the coastline and entering central China at the Yangtze River delta. Within two years, Great Britain had routed China and, during the subsequent peace treaty, extracted significant concessions: control of Hong Kong (in perpetuity), the widening of trade in new ports, and extraterritoriality for British subjects in China—a privilege obtained by American and French governments soon afterwards.

These events comprised the First Opium War, a defeat which began a era known in China as the “century of humiliation.” And only when Chairman Mao Zedong stood atop Beijing's Gate of Heavenly Peace on October 1, 1949 and proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China did this “century”—which actually lasted 109 years—come to an end.

Since then, the “century of humiliation” has been a central part of the P.R.C.'s founding mythology, of which the short version is this: Long the world's pre-eminent civilization, China fell behind the superior technology of the West over the centuries, an imbalance that finally came to a head with the loss in the Opium Wars. This begun the most tumultuous century in the country's—or any country's—history, one that featured an incessant series of wars, occupations, and revolutions and one that did not end until the victory of the Communist Party in China's 1945-49 civil war.

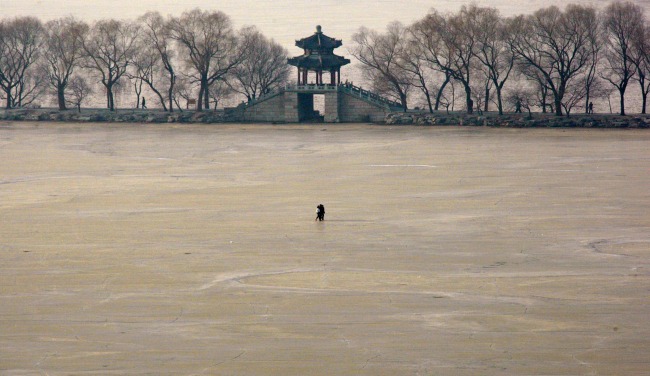

Since history is written by its winners, China's “century of humiliation” is self-serving to the Chinese Communist Party, and the country's troubles did not end in 1949. But the narrative of “humiliation” is not entirely a Chinese creation. In fact, in an episode recounted by Orville Schell and John Delury in their wonderful book Wealth and Power, during the Second Opium War in 1860 the British army set out to humiliate the Chinese by attacking Beijing's Summer Palace. Located in a northwest corner of the capital, the Summer Palace (known as Yuanmingyuan in Chinese) was an exquisite array of buildings, lakes, and parks, and served as the primary residence of the imperial court. In the Opium War, it had no military significance. But following the Chinese murder of several dozen British and French troops in an ill-conceived hostage crisis, the British took revenge by targeting the Summer Palace. Schell and Delury write:

The destruction of Yuanmingyuan was to be a “solemn act of retribution,”said the British commander Lord Elgin, in which no blood would be spilled, but an emperor's “pride as well as his feelings,” would be crushed. Indeed, before the foreign expeditionary force arrived in Beijing, the young emperor Xianfeng had already fled along with his concubine (soon to be known as the Empress Dowager Cixi) to safe haven in Manchuria. With the Son of Heaven in hiding far to the north in his hunting lodge, British and French soldiers set about teaching the Qing [Dynasty] a lesson they would never forget: that the British crown would not tolerate having the rights of Englishmen violated, even in faraway china. “As a deliberate act of humiliation,” historian James Hevia explains, “it was an object lesson for others who might contemplate defying British power.”

The systematic plunder of the palaces, which contained an enormous amount of priceless artifacts, lasted well into 1860. When it was finished, the men immediately understood they had secured a psychological victory over the Chinese:

“The great vulnerable point in a Mandarin's character lies in his pride,” [Lieutenant Colonel G.J. Wolsely, part of the British expeditionary force] observed. “The destruction of the Yuanmingyuan was the most crushing of all blows which could be leveled at his Majesty's inflated notions of universal supremacy.” Reducing the gardens to ruins was “the strongest proof of our superior strength” and “served to undeceive all Chinamen in their absurd conviction of their monarch's universal sovereignty.”

Today, a century and a half later, the Communist Party continues to preserve the ruined state of the Summer Palace as a reminder of the British plunder.

The history of war is full of many examples of where one side attacked a strategically insignificant installation in order to score a psychological victory over an opponent. But Schell and Delury's account of the destruction of the Summer Palace encapsulates just how large a role humiliation played in the last two centuries of Chinese history, and how his role in ending this humiliation forever colored Chinese impressions of Mao Zedong.