‘Something happens to the men who come here,’ says Lisa Lindell, observing the first arrivals at her drop-in centre for new parents in Malmö, Sweden. One, a straggly haired Israeli scientist, has built a perfect pyramid out of Play-Doh for his daughter. A Swedish restaurant manager is sprawled on the floor as his son presents him with various objects.

‘We think it’s a revolution,’ her colleague Karin Hallback Stigendal chimes in. ‘These daddies here, they’re very much closer to their feelings. They couldn’t harm another person. Children will change their minds, and that will be good for our society.’

Sweden is leading the fight for gender-equal parenting – men here get three months of paid, use-it-or-lose it paternity leave for each baby (in fact, many take more) – and Lisa and Karin are its warm, welcoming stormtroopers. Since they started trying to lure dads to their centre a decade ago, numbers have grown steadily until, recently, the fathers began to outnumber the mothers.

‘My patience levels have sky-rocketed,’ reports the restaurant manager. ‘There’s not so much “me” in focus any more. It’s all “him” now.’

The scientist hasn’t noticed much change, but as we bond over having given our daughters the same rare Nordic name, I’m struck by something about the way he is standing, his one-year-old perched on a stuck out hip. He’s one of a legion of Sweden’s ‘latte pappas’, as the country’s legion of scruffy men with prams are known. I’ve been one myself, taking six months off twice over the past four years to be the main carer for my daughter and then son. One afternoon in the playground, I began to notice the high, exaggerated voices many of my latte pappa acquaintances used with their babies – clear ‘motherese’.

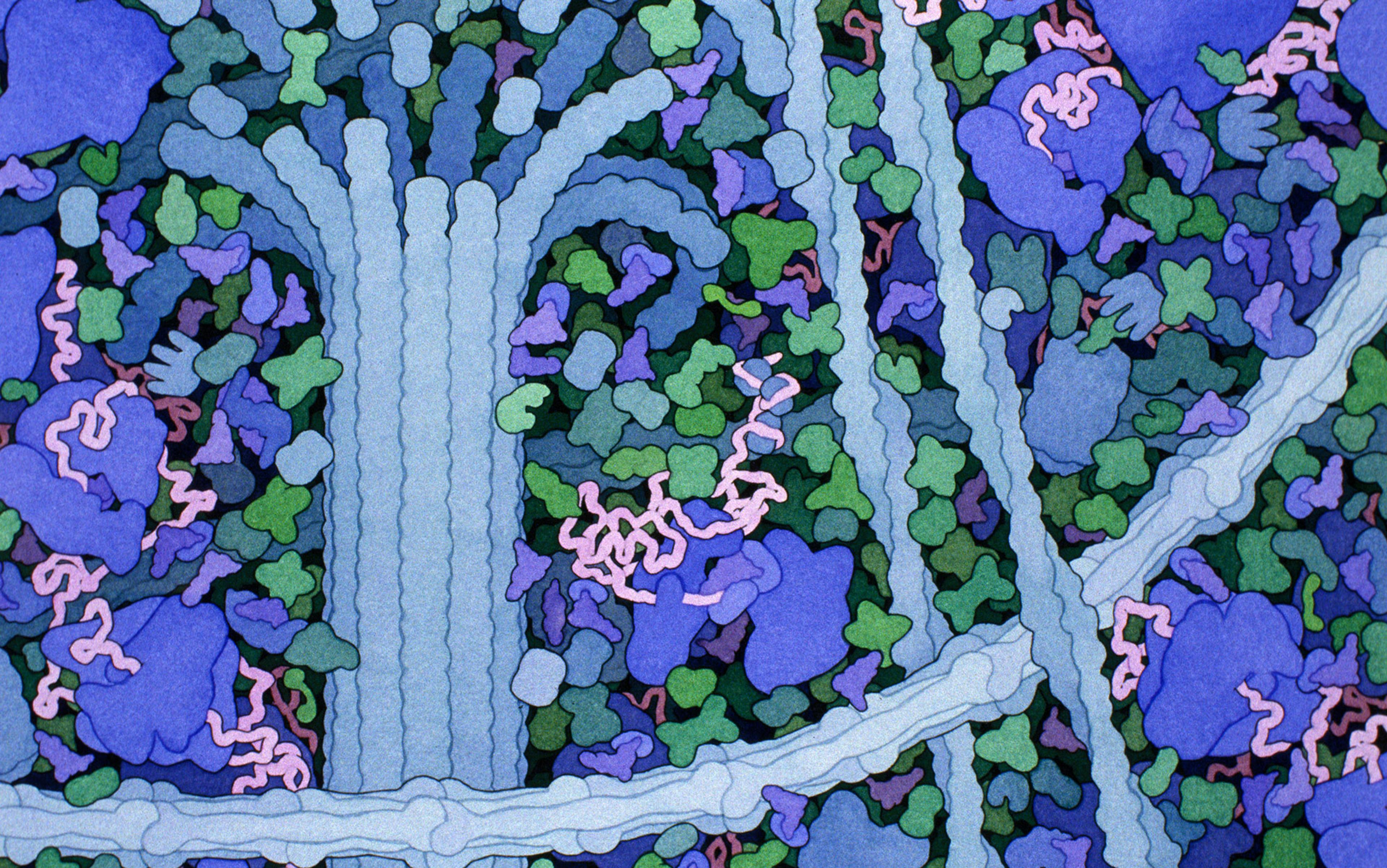

I felt compelled to find out if I was imagining it, and quickly discovered an explosion of new research demonstrating the dramatic impact that fatherhood has on men’s hormones – along with their affect and talent for staying attuned. A 2011 longitudinal study of 624 Filipino men showed evening testosterone dropping by a median of 34 per cent in the first month after becoming fathers (the most extreme case saw a drop of 75 per cent). Levels of oxytocin, the so-called ‘cuddle hormone’, almost double in fathers between the time the mothers become pregnant and the first months of fatherhood. Prolactin, the hormone that triggers lactation in women, was almost a fifth higher in fathers of infants than in non-fathers. Fatherhood also physically alters the brain. In a 2014 study, researchers scanned men’s brains in the first month after their children were born, and then again after the fourth month. It turned out that gray matter grew in areas linked to reward, attachment and complex decision-making.

These are the changes recorded in countries such as the United States, Canada and the Philippines, where mothers still do most of the childcare. But could the impact be even greater in Sweden, where men like me often take six months or more off work to be the primary carer for their babies? According to Kerstin Uvnäs-Moberg, who pioneered research into oxytocin at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden’s medical university, no one has tried to find out. ‘This is a unique experiment that we are performing right now,’ and the consequences might be profound.

Lee Gettler, director of the Hormones, Health, and Human Behavior Lab at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, and the lead author on the Philippines study, suspects that Swedish fathers might be further along the spectrum than the fathers he has studied – truly hormonally and temperamentally transformed. They would have lower testosterone than less involved dads, and their testosterone would stay reduced during the early parenting years. ‘Their prolactin might also be high, and their oxytocin would likely frequently spike up during affectionate, sensitive moments, reflecting father-child bonds and familiarity.’

I’ve seen the changes in myself. For several years, whenever my baby daughter or son made the slightest whimper at any time of night, I would find myself instantly awake and stomping over, as if controlled by a chip in my head. I’m restless and fidgety, but within a week of my first child being born I was able to rock from side to side singing ‘rock-a-bye-baby’ for hours, night after night, and I can still read my children the same story five times back-to-back without getting bored. A few years ago, there was a moment when, cradling my infant son, my nipples began to tingle strongly as if preparing to lactate.

As first one and then two children have absorbed more and more time, my life, and that of my wife, has been reduced to caring for them and working to provide for them. We rarely go out, and the only other adults we meet are those with children who can entertain our own. After a decade working in far-flung places such as India and Kazakhstan, my world has shrunk to two square kilometres of Malmö bounded by my children’s daycare, the playground, my office and my home. The strangest thing about this is not that it’s happened, but that, nestled in my warm oxytocin cocoon, I don’t mind.

Thinking about the effects of hormones on fatherhood makes my Swedish wife cringe. It seems anti-feminist, suggestive that childcare is naturally a woman’s job. This is something Uvnäs-Moberg recognises from her own work on oxytocin: ‘I was attacked, not by men but by the feminist movement,’ she says. They feared that the findings would provoke a ‘backlash, that if women have hormones, that would be a reason for pushing them back into the kitchen and to caring for children’.

Widespread response to research from the Philippines shows that these concerns are justified: media coverage has focused almost exclusively on the finding that the more new fathers’ testosterone levels fell, the less sex they had with their partners – even though parenting itself is exhausting and testosterone does not seem strongly correlated with male libido. Most popular conversations about testosterone involve ‘societal definitions of masculinity’, Gettler states.

But even some prominent researchers on fatherhood suspect that Sweden has gone too far.

Peter Gray, an anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, says that if Sweden achieved gender-equal parenting, it would be the first society ever to do so in human history. Fathers from the Aka Pygmy people of central Africa, perhaps the world’s most engaged fathers, do almost everything that mothers do, even down to suckling. But in camp they hold their babies for a creditable, but still less-than-equal, fifth of the time. ‘Sweden is asking fathers to just focus on the direct childcare, and not to have to worry about resource acquisition, and I think that might be challenging,’ Gray fears.

From my experience, though, I can tell him that it isn’t. At no point in my own combined 12 months off work did I ever feel I was doing anything unnatural or against the grain, and I have yet to meet a father in Sweden who has described feeling that way.

The flexible physiobiology governing parenting in humans likely explains my report – starting with the changes in testosterone itself. According to the Philippines study, fathers who live with their children had testosterone levels on average more than a sixth lower than those who live apart. Those who co-sleep with their children saw greater declines in testosterone than those who did not. The hormone is double-edged: testosterone makes both men and women more muscular, more likely to take risks, more socially outward-looking. Trial lawyers have higher testosterone than their office-bound counterparts. Testosterone seems to encourage people – both men and women – to take a dominant role. Less testosterone, on the other hand, has a mellowing effect. A 2014 study of Israeli fathers found that those with lower levels of the hormone were more affectionate, tactile and communicative with their infants, and more frequently used that motherese.

Then there’s the power of oxytocin. ‘There are multiple pathways to increase your oxytocin levels and to ignite the parental brain, and there are pathways for fathers which can make that system work just as well as in mothers,’ says the developmental neuroscientist Ruth Feldman of the Bar-Ilan University in Israel. In the past, she points out, many mothers died in childbirth, ‘so evolution must have tailored the parental brain as something very, very flexible and adaptive.’ Far from transgressing some natural role, human fathers’ engagement in direct childcare might have been crucial to our evolutionary success.

the longer the leave that fathers took with their babies, the more they saw them later in life, even if they had separated from the mother

Traditional fatherhood is enhanced by hormones, too. Vasopressin and prolactin have been associated with ‘orienting infant attention to objects and the outside world’, Feldman explains. A 2010 study by Ilanit Gordon and colleagues at Feldman’s lab, found that the higher the base prolactin levels of fathers, the longer the bouts of exploratory play they engaged in with their children. In birds, prolactin seems to be involved in more indirect forms of paternal support, so-called ‘provisioning’. Some seabirds maintain high levels of prolactin over long voyages, perhaps to increase the chance of their returning to their young. Gettler points to research showing that human fathers with higher prolactin are also more alert and responsive to infant cries. Feldman has spent the past six years studying gay couples who father children with surrogate mothers, and she has yet to find any difference between their offspring and those of heterosexual parents, which suggests to her that at least one of them is doing everything that a mother does.

‘A higher level of oxytocin directs you to focus more on play that is face-to-face, and vocalising, and this kind of affectionate contact,’ she reports. ‘For mothers, it comes more naturally, because pregnancy makes your whole brain soak in oxytocin. For fathers, it’s much harder work. If, for 10 minutes before you go to your newspaper and television, you play with a well-fed and bathed infant, you know – “I’d like to see my kid when I’ve come back, between my pipe and my New York Times” – that’s not going activate any hormones.’ Triggering oxytocin takes physical contact, particularly skin-on-skin.

And to any men still smirking at the hit that engaged fathers seem to be taking to their testosterone, take note of this: dads involved enough to garner the full hormonal effect will be rewarded by a more intense bond with their children, throughout life. One Swedish study from 2008 found that the longer the leave that fathers took when their children were babies, the more they saw them later on in their lives, even if they had separated from the children’s mother.

But what happens to Sweden’s latte pappas when they return to their workplaces, their brains marinading in oxytocin and prolactin? How many, like me, find their priorities shifting in subtle but significant ways?

When Uvnäs-Moberg had her own children, the effects were so powerful that it changed the direction of her academic career. ‘That’s why I started to work with oxytocin, because I noticed these differences, in emotion but also in priorities,’ she says. ‘I was a scientist, working with the gastrointestinal tract, but that wasn’t interesting any more.’

This might be one reason why some women who have fought tooth and nail to rise up in competitive careers abandon those careers without qualms once they have a child. Could something similar be happening to Sweden’s latte pappas?

Uvnäs-Moberg describes oxytocin as the opposite of the fight-flight system. ‘It is the calm and connection system: you reduce your arousal, you become calm, and you become friendly and not so anxious, and also your blood pressure gets lower. Your need to be at the top of a hierarchy decreases, and you become more interested in social networking and other affairs. That may be good when your babies are small, but after five years you may regret it.’

a temporary lull in the competitive drive of returning fathers is more than made up for by the retained expertise of the mothers better able to continue their careers

It could be that anyone, male or female, who combines parenthood with competitive careers and positions of power will, as a result, be a less patient and attentive parent. There might be a trade-off between being a status-hungry careerist and a nurturing parent, whatever your gender.

‘You as a journalist have flexibility, but I’m sure that if you are the head of an investment bank, it could be catastrophic,’ Uvnäs-Moberg argues. ‘What I see in the institutions where I’ve been working is that the real careerists don’t do this. There is a group of men that are so testosterone-linked, that I don’t think they will ever stay at home with the children.’

Yet big Swedish companies such as the tech giant Ericsson actively encourage their male workers to take longer parental leave, which suggests that Sweden’s latte pappas remain useful employees. Perhaps a temporary lull in the competitive drive of returning fathers is more than made up for by the retained expertise of the mothers better able to continue their careers.

Back at the drop-in centre, Lisa and Karin remain convinced that giving all fathers a six-month dose of hands-on parenting would vanquish forever the brash, aggressive, insensitive man. ‘If you are closely connected to a child,’ Karin says, ‘you can’t be tough and hard.’

Soon, the assembled mammas and pappas begin squeezing themselves into the centre’s back room for the daily singing session. As they come to the final rousing ballad, which everyone sings while wafting a multicoloured parachute in the air, memories well up of the hundred or more mornings I must have spent in this room, rocking from side to side with either my daughter or my son on my lap. Whatever the final impact of Sweden’s experiment on fathers, there’s one latte pappa who will never be the same again.