When Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko returned from space last week after 340 days, they showed few outward signs of fatigue. Moreover, they had the self-satisfaction of putting in nearly a year of very hard work on the International Space Station. Their efforts, along with those of hundreds of scientists on Earth, will undoubtedly advance our knowledge of the effect of long-duration spaceflight on human health.

But to call Kelly and Kornienko pioneers in the truest sense of the word, as those who ventured into the truly unknown, would be a disservice to the Russian cosmonauts who did so much more than two decades ago in more cramped, less comfortable conditions aboard the Mir space station.

Before NASA’s one-year mission, four Russian cosmonauts had spent a year or more in space, beginning with Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov in 1987. Russian and Kazakh space officials were quick to remind Kelly and Kornienko of this last week after they landed in a remote area of Kazakhstan.

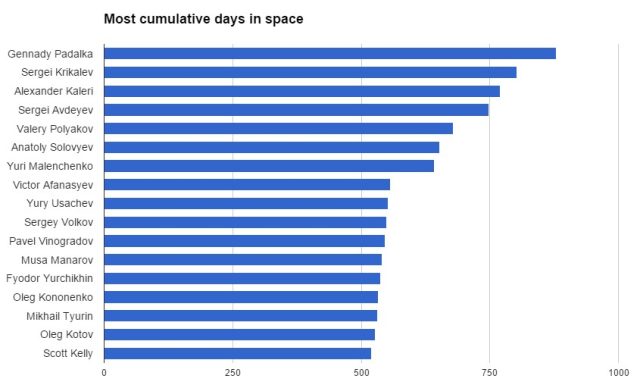

After the pair underwent a few medical tests they flew by helicopter to Dzhezkazgan in Kazakhstan for a ceremony. After being with presented a traditional meal of bread and salt during a ceremony former cosmonaut Talgat Musabayev, the current head of the Kazakh space agency, KazCosmos, addressed them by saying, “Congratulations on your record. Of course it was already done 28 years ago.” This was not quite a hero’s welcome, but Russia is rightly proud of its spaceflight heritage when it comes to endurance. After all, even with two long stints on the space station of six months and now more than 11 months, and setting the US record for spaceflight duration, Kelly only ranks 17th on the list of astronauts and cosmonauts with the most accumulated time in space.

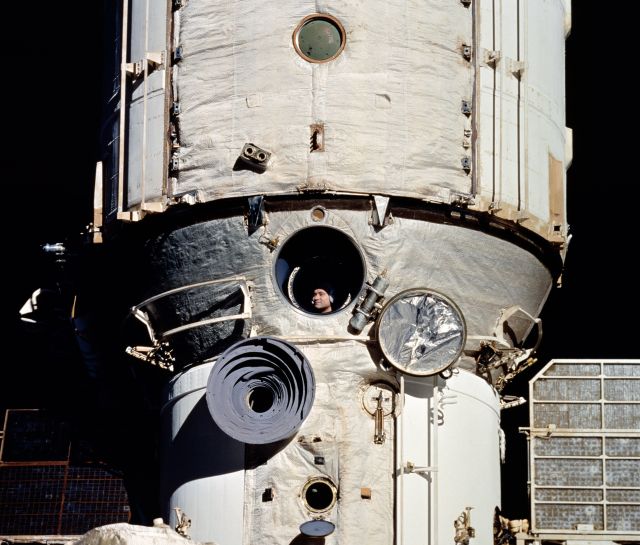

And the Russians have indeed endured. Before the United States and Russia partnered to build the International Space Station (ISS), the Russians had the Mir Space Station, which operated from 1986 to 2001. It was smaller, less well-maintained, and had fewer amenities than the comparatively larger ISS. And no one spent longer in a single spaceflight aboard Mir than Valery Polyakov, who lived there for 438 days in 1994 and 1995.

Before he landed, Ars asked Kelly whether he could have stayed another 100 days, as Polyakov did on Mir. “I think it’s a little bit of a different experience being on this space station,” Kelly said. “We have better connectivity with people on the ground, and the environment is a bit more comfortable. I really respect what he did back then, obviously. But yeah, I could go another 100 days. I could go another year if I had to.”

Mir was far from the buttoned-down environment of the ISS. If the equipment was older and more prone to failure, cosmonauts and astronauts had more freedom. They were able to drink freely, imbibing alcohol such as vodka and cognac, and there were reports of cigarette smoking. Because cosmonauts spent a majority of time keeping the outpost in serviceable condition, there was also less time for science.

But that didn't stop the Russians from doing some groundbreaking research. And none more so than Polyakov, a physician who specialized in the health of astronauts. He volunteered for such a long mission because he wanted to study the effects of long-duration spaceflight on the human body firsthand. While in space, he underwent a battery of medical and psychological tests, although these were not as in depth, nor did they have the benefit of modern medical science like the NASA one-year mission.

Perhaps the most interesting scientific result of Polyakov’s 438 days in space was his mental state. He was assessed 29 times during his mission with a variety of mental tasks, from grammatical reasoning to mood assessment. After comparing his mental state during pre-flight, in-flight, and post-flight conditions, the physicians found no cognitive impairment during the mission.

However, they noted two distinct periods of a somber mood and a feeling of increased workload. This came during the first three weeks in space and then during the first two weeks after returning from space. According to the authors of a study in the journal Ergonomics that assessed his performance, Polyakov displayed “An impressive stability of mood and performance during the second to fourteenth month in space, where mood and performance had returned to preflight baseline level.”

What this suggests is that after a period of adjustment, Polyakov adapted to space; its routines, workload, and the absence of gravity became a new normal. This bodes well for humans if we can ever fashion a coherent space policy that puts us on a credible journey to Mars. Picking the right astronauts—the Polyakovs and Kellys—will ensure they have the mental and physical fortitude to see through such an arduous journey.

As for Polyakov, he was ready to go even after landing in the spring of 1995. Instead of being carried from the Soyuz spacecraft to a nearby chair, as is customary, he walked. Not bad after nearly 15 months in space.

reader comments

76