Dan Kelly (bushranger)

Dan Kelly | |

|---|---|

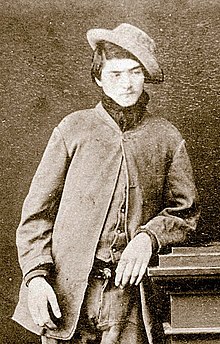

Dan Kelly, most likely 1877 | |

| Born | Daniel Kelly 1 June 1861[1] Beveridge, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 28 June 1880 (aged 19) Glenrowan, Victoria, Australia |

| Occupation | Bushranger |

Daniel Kelly (1 June 1861 – 28 June 1880)[1] was an Australian bushranger and outlaw. The son of an Irish convict, he was the younger brother of the bushranger Ned Kelly. Dan and Ned killed three policemen at Stringybark Creek in northeast Victoria, near the present-day town of Tolmie, Victoria. With two friends, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, the brothers formed the Kelly Gang. They robbed banks, took over whole towns, and kept the people in Victoria and New South Wales frightened. For two years the Victorian police searched for them, locked up their friends and families, but could not find them. Dan Kelly died during the infamous siege of Glenrowan.

More books have been written about the Kelly Gang than any other subject in Australian history. The Kelly Gang were the subject of the world's first full-length feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, made in 1906.

Early life[edit]

Dan Kelly's father, John Kelly (known as "Red"), married an Irish woman, Ellen Quinn, in Melbourne in 1850.[2]: 74 They had seven children: Annie (1853), Edward "Ned" (1854), Maggie (1856), James (1859), Dan (1861), Kate (1862) and Grace (1863).[2]: 75 [3]: 9

In 1864, Kelly's family moved north to a farm at Avenel. Red Kelly stole a calf and was sent to jail for six months.[2]: 75 Dan was in trouble with the police when he was five years old because they believed he had stolen a horse.[2]: 75 Dan's father died in 1866, and in 1867, his mother, Ellen Kelly, moved the family to a small farm near Greta in north east Victoria.[3]: 30

Ellen Kelly's two sisters, Catherine and Jane Lloyd, were living at Greta, and her two brothers, John and James Quinn, had moved to the area in 1864.[3]: 30 The Quinn family were well known to the police. Dan Kelly was again in trouble with the law when he was only 10 years old. He and his brother James, aged 12, were arrested by Constable Flood for riding a horse that did not belong to them. Jim was working for a local farmer and had taken the horse to ride home on. Flood did not believe them, and the boys were forced to spend two nights in a prison cell.[2]: 82 It later transpired that the farmer had given them permission to borrow the horse. In 1875, like many other young men in north east Victoria, Dan Kelly and his cousins, the Lloyds, went to New South Wales to look for seasonal farm work in the Riverina area and on the Monaro High Plains.[3]: 59 His group of friends were known as "the Greta mob".[3]: 59 They went out together to hotels, dances and horse races. By 1876, they were well known for their visits to nearby towns such as Wangaratta, Beechworth and Benalla.[3]: 59

On one visit to Benalla in 1876, Dan was arrested for stealing a saddle. The police let him go when they could not get enough evidence.[3]: 59 Dan and his cousins got into trouble with the police in October 1877. They had gone to a shop to pick up food and other supplies, but the shop was shut. When the owner refused to open the shop, Dan Kelly broke down the door.[3]: 52 They were charged with violent assault, damage to property (the door), breaking into houses and stealing things worth £113. The boys went into hiding, and the police spent three weeks looking for them. Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick told Ned Kelly to get them to give themselves up.[3]: 52 In court, the police were not able to prove most of the charges, but Dan went to prison for one month for damaging property worth £10.[2]

On 15 April 1878, Constable Fitzpatrick, went to the Kelly's house to arrest Dan Kelly for stealing horses. Dan had been seen in Chiltern riding a stolen horse.[3]: 52 What happened at the house is now called the "Fitzpatrick incident". There was a fight with Fitzpatrick, and he said the Kelly family had tried to kill him. Dan and Ned went into the bush to hide. Ellen Kelly was sent to gaol for three years for attempted murder. Maggie's husband, William Skillion, and a neighbour, William Williamson, were sent to gaol for six years.[3]: 63

Kelly Gang[edit]

Ned and Dan Kelly went into the bush to a place in the Wombat Ranges. Dan Kelly had built small huts some time earlier on Bullock Creek, where he had cleared an area of about 20 acres (8 ha) to keep horses.[4] He had also built a small still for making alcohol.[2]: 89 The brothers spent their time searching for gold in the creek.[4]

During the months they were hiding at Bullock Creek, they were often visited by their friends including Steve Hart, Joe Byrne, Aaron Sherritt and the Lloyds.[3]: 78 The police took the charge of attempted murder very seriously. A reward of £100 was offered for the capture of the two Kelly boys.[5] The police thought the brothers were hiding in the Wombat Ranges. In October 1878, they sent two search groups out to find them. One group travelled south from Greta, and the other started from Mansfield and travelled north.[2]: 90

Stringybark Creek[edit]

The Mansfield group was led by Sergeant Michael Kennedy, with three policemen; Constables Thomas McIntyre, Thomas Lonigan, and Michael Scanlon. They set up a camp at an abandoned diggings at Stringybark Creek in a thick forest area.[6] Kennedy and Scanlan went searching for the Kellys, while Lonigan and McIntyre remained at the camp.[2]: 95 The Kellys were living in a hut close by at Bullock Creek. They heard gunfire and discovered the police camp. They decided to capture the policemen and take their guns and horses.

Ned and Dan, and friends Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, went to the police camp and told them to surrender.[2]: 96 Constable McIntyre put his arms up, but Lonigan tried to run for cover. Ned Kelly shot him dead as Lonigan turned his head back toward Kelly as he ran.[2]: 96 When the other two police came back to camp, McIntyre told them to surrender. Scanlan was trying to dismount when he saw the attackers and tried to swing his rifle around but Ned shot him dead.[2]: 97 Kennedy jumped behind his horse and ran shooting from tree to tree with Ned chasing him. During the shooting, Kennedy was wounded. Ned shot him in the chest when he tried to surrender some 800 yards away from the camp. Then he lined him up and then shot him through the chest at point blank range.[2]: 97 McIntyre was able to escape during the confusion. It was later reported in the newspapers that it was Dan who had shot Kennedy.[2]: 98 Dan was wounded during the shooting.[2]: 100

Outlaws[edit]

The Victorian government passed a law on 30 October 1878, making the Kelly Gang outlaws; they no longer had any legal rights. They could be shot by anyone, at any time, without warning.[2]: 103 Anyone who could capture one of the Gang, alive or dead, would be paid a reward of £1500.[2]: 103

The bushrangers were seen at several places around north east Victoria. They had tried to cross the Murray River into New South Wales, but the water was too deep. The police had several large groups hunting for them. On 10 December, the Kelly Gang robbed the bank at Euroa.[2]: 110 In February 1879, they went to Jerilderie, New South Wales. They locked the town's policemen in the police station cells, and kept many people hostage in the Royal Mail Hotel for three days. Dan Kelly and Steve Hart kept the people in the hotel, while Ned Kelly and Joe Byrne robbed the bank.[3]: 121 After the bank robberies, the reward was increased to £2,000 for each man, or the larger amount of £8,000 for the Gang.[3]: 128

Over the next 18 months many policemen were sent to north-east Victoria to search for the Kelly Gang.[3]: 140 The police could not find the bushrangers because they were badly led and they did not know how to live in the bush. However the Kellys were experts in living in the bush and they had the support of some local people.[2]: 151

Murder[edit]

In June 1880, the Kelly Gang came out of hiding. They knew that Joe Byrne's friend, Aaron Sherritt, had been giving information to the police. Four policemen were staying at Sherritt's house, near Beechworth, to protect him. Dan Kelly and Byrne went to Sherritt's house late at night and took hostage his neighbour, a German called Weekes and used him to trick Sherritt out of the house. When Sherritt opened the door, Byrne shot him dead.[2]: 155 The policemen were hiding under the bed. Kelly and Byrne rode quickly back to Glenrowan where Ned Kelly and Hart had forced many of the town people into a hotel, the Glenrowan Inn.[7] They also had forced railway workers to pull up the train tracks. They knew that more police would be sent by train to Beechworth to find them. They wanted the train to crash when it reached the place where tracks had been removed near Glenrowan.[7] The bushrangers, wearing homemade armour, would then capture any of the policemen that were alive after the crash.[2]: 153 With the police out of the way, the Kelly Gang would then go into Benalla and rob the bank.[2]: 153 The captured police would be released when Ellen Kelly, William Williamson, and William Skillion, were let out of gaol.[2]: 153

The plan did not work because the four policemen did not come out of Sherritt's house until the morning.[2]: 156 This meant that the news of the murder did not reach Melbourne as quickly as the Kelly Gang had hoped. The people held prisoner in the hotel became restless. Ned organised music and Dan joined in dancing to keep the people in the hotel entertained.[8] Dan also organised some sporting games including long jump and hop, step and jump.[3]: 160 Dan wanted to leave Glenrowan when they knew the plan was not going to work because the train was late.[9] Ned Kelly let Thomas Curnow, the school master, go home to his wife. Dan told his brother not to trust Curnow, and to keep him at the hotel.[9] Curnow did go home, where he discussed with his wife about doing something, but after hearing the train approaching, he ran to the railway line with a lantern and his wife's red silk scarf and at about 3.00am he was able to stop the train before it reached the broken rails.[2]: 158 The police quickly left the train and placed themselves around the hotel so that the Kelly Gang was trapped inside.[7]

Glenrowan and death[edit]

When the bushrangers heard the train pull into the station, they knew their plan to destroy the train had failed. They put on their suits of armour and went on to the verandah of the hotel to wait for the police.[2]: 159 In the first few shots, police Superintendent Hare, Ned Kelly and Joe Byrne were wounded, and Jack Jones, son of the hotel owner, was fatally wounded. Ned Kelly, who was dressed in his armour, was able to leave the hotel and kept shooting at the police. The police fired their guns into the hotel building for seven hours. It is estimated that 15,000 bullets were fired during the shooting.[10] Byrne died after being shot in the groin. Ned Kelly went back to the hotel but he could not find Dan or Steve Hart who were hiding in a back room. He again left and tried to find his horse. Ned Kelly was shot in the legs as he searched outside for his brother.[2]: 162 The police were then easily able to capture him.

At 10.00 am there was a large crowd of people watching the action. Police Inspector Sadleir was forced to stop the shooting to allow many of the hostages to escape. He would not let Dan's sister Maggie, or a Catholic priest, Father Gibney, go into the hotel to tell the men to give themselves up. Instead, he ordered that a cannon be sent from Melbourne so that they could destroy the hotel.[2]: 162

At 2.30 pm, the police set fire to the building to try to make the rest of the Kelly Gang leave the building.[3]: 189 Father Gibney ignored the police and went into the burning building.[2]: 162 He found Dan Kelly and Steve Hart dead in a back room of the hotel. He said their bodies were lying side by side, their heads resting on blankets.[2]: 162 Byrne's body was dragged out of the hotel, but the bodies of Hart and Kelly were badly burned during the fire. People who saw the burned and blackened bodies were only able to tell which was Dan Kelly and which was Steve Hart by their size.[3]: 30 They were placed on sheets of bark from a tree and photographed. Three Glenrowan people held hostage inside the hotel died during the siege.[2]: 159–163

Family members, including his sisters, Kate and Maggie, and friends took the bodies back to Greta.[3]: 195 The police tried to get the bodies back, and sent a group of 16 policemen to Greta, but they became worried that this would start another fight and they went back to Benalla.[3]: 208 Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were buried in unmarked graves at Greta, on 30 June 1880.[2]: 164 About 100 people were at the funeral, with Dan's cousin Tom Lloyd as the undertaker, and a Greta farmer, Daniel O'Keefe, acting as a preacher. After the graves were filled in, the whole area was ploughed over to keep the site of the graves hidden.[3]: 206 The family was worried that the police would still try to get the bodies.

After Glenrowan, Dan Kelly and Steve Hart's armour was taken by the troopers and kept at Benalla.[11] Ned Kelly's armour was sent to Melbourne to be used at his trial. Joe Byrne's armour was sent to the police depot in Richmond. At the end of 1880, all the pieces were in Melbourne. One set of armour was given to Sir William Clarke.[11] Over the years the pieces became mixed up. In 2002, the State Library of Victoria and the police exchanged some pieces to try to get the sets complete.[11] The State Library has Ned's armour, Joe's is still owned by the Clarke family,[12] and the police have Dan and Steve's armour, which can be seen at the Victoria Police Museum in Melbourne.[13]

In 2012, it was reported a gun that may have been Dan Kelly's and used at Glenrowan was to be sold at auction.[14] It was sold to a private bidder for AUD $122,000[15]

After Glenrowan[edit]

There was no autopsy held on Dan or Steve, and there have been many stories about what might have happened. The arrangement of their bodies in the hotel suggests they may have killed themselves.[5] This was the story that was used in the first Kelly film, The Story of the Kelly Gang in 1906,[16] and in the 2003 Ned Kelly movie.

Despite his body being identified by police and a priest before being burnt, there have also been stories that both Dan and Steve survived the fire.[17] There is little evidence to support these claims.[18][19] One man, James Ryan, said he was Dan Kelly. In 1934 he went on stage at the Brisbane Exhibition and told stories about the Kelly Gang. He died on 29 July 1948, after being struck by a train.[20] The Ipswich City Council have put a memorial on his grave. In 2001, scientists took a small piece of bone from the grave of Charles Devine Tindall at Toowoomba, Queensland, to see if they could find DNA to prove he was Dan Kelly.[21] Devine, who had burn scars on his body, told his family he was really Dan.[22] He said he had hidden under the floor of the Glenrowan hotel and escaped after the fire.[21] An archaeological dig at the site of the hotel by Adam Ford in 2008 found that there was no cellar or other hiding place under the floors.[23] In October 1902, a Melbourne newspaper printed a story that Dan Kelly and Steve Hart were living in South Africa.[24] The men had fought in the Boer War. Another man, Jim Davis from Darra (a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland), said in 1938 that he was Dan Kelly. He claimed that he, Steve Hart and Joe Byrne had escaped from the hotel.[25] He also said he was born at the Eureka Stockade in 1854, which makes him too old to have really been Dan. "There are three people alive today who met Dan or Steve. Mr John Harris and Vince Allen both met Dan Kelly. Vince (now 82) met Dan at Main Junction in 1944. Then Helen Stanwick, now 103 met Steve Hart (who called himself Harry Thompson – who was also treated by Dr Harry Power at Devil's Pulpit) when she was a young woman. I have many emails and photos which are testimony that these two men escaped the hotel fire at Glenrowan."

Cultural references[edit]

The story of the Dan and Ned Kelly has been told many times. There have been more books written about the Kelly Gang than any other event in Australian history.[3]: 9 The very first full-length film in the world, made in 1906, was The Story of the Kelly Gang.[26]

In the 2019 film True History of the Kelly Gang the part of Dan Kelly was played by Earl Cave, with Ned Kelly played by George MacKay. In the 2003 Ned Kelly movie starring Heath Ledger as Ned Kelly, the part of Dan Kelly was played by Irish actor Laurence Kinlan.[27] Allen Bickford portrayed Dan Kelly in the 1970 film Ned Kelly, with Mick Jagger as Ned Kelly.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Kelly, Daniel (Dan) (1861–1880)". Obituaries Australia. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af McQuilton, John (1979). The Kelly Outbreak, 1878 — 1880. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84180-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v McMenomy, Keith (1984). Ned Kelly – The authentic illustrated story. South Yarra, Victoria: Currey O'Neill Ross. ISBN 0-85902-122-X.

- ^ a b "Kelly Gang Camp Site". Heritage Places and Objects. Heritage Council of Victoria. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ a b Barry, John V. (2006) [1974]. "Edward (Ned) Kelly (1855–1880)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 5. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ "Stringybark Creek site". Heritage Places and Objects. Heritage Council of Victoria. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ a b c "Glenrowan Heritage Precinct". Heritage Places and Objects. Heritage Council of Victoria. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ Sheppard, Barrie (2000). Ned Kelly. Melbourne, Victoria: Heinemann Library. p. 23. ISBN 1-86391-971-6.

- ^ a b "Dan Kelly". The Kelly Gang. Iron Outlaw. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ "Bullets from Ned Kelly's shoot-out at Glenrowan found". heraldsun.com.au. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ a b c "Kelly Armour Fact Sheet, State Library of Victoria". 2011. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Oldis, Ken (2000). "The True Story of the Kelly Armour". The La Trobe Journal. State Library of Victoria. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ "Victoria Police Museum". Victoria Police Museum. 19 February 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Elder, John (10 November 2012). "'Possible' Kelly pistol up for auction". The Age. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Webb, Carolyn (21 November 2012). "Dan Kelly gun sells for $122,000". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "National Film and Sound Archive — Restoration of The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906)". nfsa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ Allen, Vince (2003). "Dan Kelly". halenet.com.au. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Delros, Marion (5 July 2005). "Two of the Ned Kelly Gang survived ambush and lived on for years, says historian". The Independent on Sunday. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Cowie, N. (2002). "Dan Kelly News". Bailup. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ Tully, Paul. "Queensland History – The Kelly Gang". Ipswich City Council. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Grave said to contain remains of Dan Kelly". Iron Outlaw. 27 September 2001. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ "Did Ned Kelly's brother survive Glenrowan shoot-out?". ABC News. 25 June 2005. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Terry, Paul (2012). The true story of Ned Kelly's last stand. Sydney, Australia: Allen and Unwin. p. 221. ISBN 9781743310069.

- ^ "The Kelly Gang. An extraordinary yarn". The Argus. 15 October 1902. p. 7. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ "Did the Kelly Gang perish at Glenrowan?". The Queenslander. 22 June 1938. p. 7. Retrieved 20 March 2010.

- ^ Hogan, David (7 February 2006). "World's first 'feature' film to be digitally restored by National Film and Sound Archive" (Press release). National Film and Sound Archive. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ "Laurence Kinlan". Filmbug. 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

External links[edit]

- The Ned Kelly Trail Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine – has many photographs of Ned Kelly linked places and items.

- Photograph of Dan Kelly at the State Library of Victoria

- Bill Denheld's website on Stringybark Creek, with maps and photos

- Photograph of the Glenrowan Inn Archived 30 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Photograph of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart's armour Archived 30 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Photograph of Dan Kelly's body after the fire

- Photos of the archaeological dig at Glenrowan in 2008