Ben Katchor is one of nature’s purest New Yorkers. A canny observer of the current situation in the city and, at 64, a meticulous observer of the ways it has changed over the years, Katchor won the MacArthur “genius” grant in 2000, making him one of a handful of cartoonists ever to have received the honor.

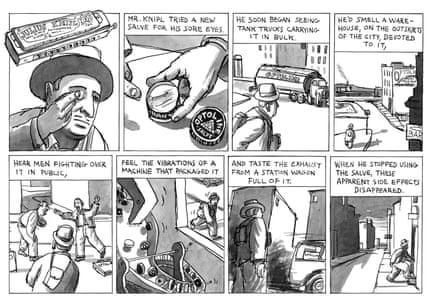

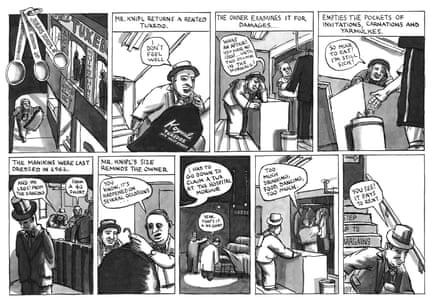

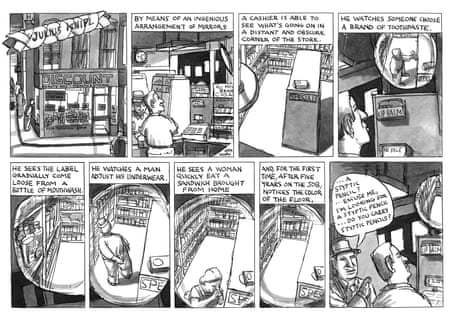

Katchor’s cartoons, for years mostly available in small alt-weekly newspapers in the US, are paeans to unglamorous jobs or explanations of businesses that really ought to exist. At the moment, he teaches his craft to students at the city’s New School, where he frequents a coffee shop across the street straight out of one of his own cartoons. Katchor’s pace has slowed – instead of his weekly Julius Knipl strips, he now draws a strip once a month for Metropolis – but the force of his intellect is undimmed.

With Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns and Chris Ware, Katchor is a member of the generation of alternative cartoonists whose literary ambitions revolutionized a faltering underground comics world in the 1980s and 90s. This fall, his first long-form comics work, Cheap Novelties, is back in print from Drawn & Quarterly in the US and Jonathan Cape in the UK, packaged as Cheap Novelties: The Pleasures of Urban Decay with a set of strips never before reprinted.

You were at the birth of what people used to call alternative comics and now often call literary comics. What’s it like to look at your old work?

It was a period when there were endless possibilities. I hadn’t done a weekly strip and there were all these subjects to talk about; it seemed inexhaustible. It was really easy to do the first few years of the strip. And then as I sort of went through this list in my mind of topics, it became more difficult because I’d say, “Oh, I’ve done a strip about that.” And so, you know, I don’t know. Who reads their own work? I just figure it out, and it’s a relief to have figured it out. It’s not for me to read. There’s a million things to look at and read. I would only see the flaws in it.

It’s done like writing for a newspaper, on deadline. So I put off all week doing it, hoping I come up with a better strip.

What made for a good Julius Knipl strip?

A great revelation. And that’s really hard to do for me. When you hit them, then they’re good. There’s a minimum level of revelation that’s worth publishing. I think whatever you do on a serial basis like that, there’s a standard you don’t want to sink below so you can say, “At least there’s some technical ability or craft I have and it’ll be at that level.” It may not be a great one, but it’ll be good.

Your stuff doesn’t look like anybody else’s in comics.

That’s because I was looking at 17th-century draftspeople and not comics. [Nicolas] Poussin, and Rembrandt, and the whole other world of anything but commercial art. I grew up reading comics, but then I discovered a whole other world of picture-making. They didn’t all make comics, but they made heavily narrative pictures. Poussin was a philosopher-painter, he wasn’t just a painter, so there was a big literary angle to these images. So I looked at that. That’s what was always interesting work.

You can’t keep recycling what’s happening. The critique was that I didn’t like how most comics were drawn and I had to draw differently than they did. If you don’t have a critique of what you’re doing, you may as well not do it. Just go on and be an apprentice to somebody and do what they do. That’s a pretty deadly direction to go in. Robert Crumb was looking at Albrecht Dürer, and looking at Doré and these incredible draftsmen of the 19th century. He was looking at early newspaper comics.

What did you do when the strip was first starting out?

I had a typesetting company with a few friends. We did really low-level graphics downtown, and we did it just so we wouldn’t have to have jobs. We started this company and we had our own weird hours.

Who else was in there with you?

Two friends of mine. We knew each other from comic fandom. I really saw the inside of small, desperate businesses because our customers were all small, desperate businesspeople. It was kinda fascinating to see that firsthand. I was living in one of these cheap, unoccupied loft buildings. My overhead was very low at that time. As soon as I could make enough money, I stopped doing that and did comics.

Who were your clients?

Local coffee shops. We did everything like that. These printers came to us with these little stickers that said “genuine 14-karat gold”, probably to put on fake watches! Mainly for offset printing. This is all pre-digital technology – photo and typesetting just before digital typography. We did newspapers for small organizations – [it was also] pre-desktop publishing; people couldn’t typeset their own newspapers.

So much of your work is about odd businesses. Has development hurt those kinds of businesses?

I did a strip about it, called the Committee for Architectural Neglect. It’s about a group of people who should be put in control of buildings and not want to develop them and keep them at a certain level of development. Stop restoring them! Stop making them cheap places to live! But that’s as far-fetched as a socialist utopia. I don’t know if there is one that wasn’t built on the ruins of something else.

I have nothing against a centralized coffee distribution service in this country. Maybe they’d let the government run it, and let each neighborhood run it the way they’d like to run it. Starbucks, chains like that, it’s just such a loss. It’s such a whaddayoucallit, an absence of imagination, that you just duplicate the thing you’re doing in another place. That’s appalling. If there were state-run coffee bars, at least somebody would say well wait a minute, everything is different. Some neighborhoods would have cafe con leche and some neighborhoods would have Vietnamese drip. They would never just say “it has to be the same”. That would be unthinkable, but that’s what we have. It’s kind of standardized.

It’s beyond my understanding why anybody with money who wants to be in the coffee business wouldn’t hire really inventive people. Then nobody would hate them!

What was it like to be there in the beginning of the ‘alternative comics’ movement?

It seemed like it was career suicide to do comics! You’re not in the world of painting, you’re not in the world of literature, you’re in the world of trashy things. It had such a bad connotation to most Americans. So the thing is, it needed to be critiqued as a form. You can say, “I can talk about this in this form! It doesn’t need to be this high-contrast, commercial art. It can look like an 18th-century wash drawing. It can be anything you like!” It sounds pretty obvious now that you should do that, but no. As comics began to get this kind of notice in the literary world, all these people, painters, would say to me, “I could have done comics too, but at the time it was suicide! I wanted to have a career. I didn’t want to do comics, I wanted to be taken seriously as a painter.”

There’s kind of a purity of mission to it, though, among guys who decided to do it when it was disreputable. Because you weren’t doing it for recognition, you were doing it because it was interesting.

I grew up reading comics, and then I went and studied painting and literature, and I knew what painting was about – you know, this kind of idea of purifying a medium – and I said, “This is a dead end,” and I went back to this childhood interest of mine, this thing that predates modernist painting concerns.

What do you mean when you say painting is about purifying a medium?

Well, modernist concerns were to make paintings that were not about other things, they were just about pure, retinal painting, and it led to minimalism and it led to conceptual art. You know, we’re now in some rethinking of that – postmodernism. That had a really heavy effect on people who make pictures, that there’s such a thing as media specificity. I think it’s a misreading of an early theorist called [Gotthold] Lessing, who said these things work in different ways: writing works in time and pictures work in space – don’t confuse them. Don’t try to do in pictures what you should be doing in writing.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion