Is it time for an "education spring"? One senior and much respected educationalist, exasperated by overbearing political interference, a data-driven, high-accountability culture and a schooling system that does not come close to meeting the needs of all young people, is hoping that an uprising from the teaching profession is on its way. Mick Waters, curriculum guru and former director at the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, is calling for a rethink of the purpose and aims of education.

"A consensus needs to be built around the purpose of schooling and how it fits within the overall education of pupils. We need to define better the aims and purposes of schooling," Waters said at a Westminster seminar last week, attended by union leaders, teachers, headteachers and MPs. "We need to be clear about aspiration as an outlook of worth, contribution and spirit, rather than simply exam passes and careers."

But how likely is it that the teaching profession will answer the call? One green shoot that suggests they might is teacher Debra Kidd, also present at the Westminster seminar, who is behind a petition – to which thousands of teachers have added their names – to block proposed curriculum reforms.

Kidd, an advanced skills teacher for pedagogy and a former senior lecturer in education, has also launched the Calling All Parents petition to raise awareness outside the teaching profession of what she feels are potentially damaging reforms. The campaign aims to stop politicians, namely the education secretary, Michael Gove, from introducing policy or promoting messages that aren't rooted in evidence, to refrain from using derogatory language to describe teachers, children and parents and to reconsider the decision to allow unqualified staff to teach in academies and free schools.

Waters's vision also includes big strategic changes such as a national council for schooling, an independent education body – at arm's length from parliament and ministers – that would manage funding, work with parents and the profession and help share innovative practice.

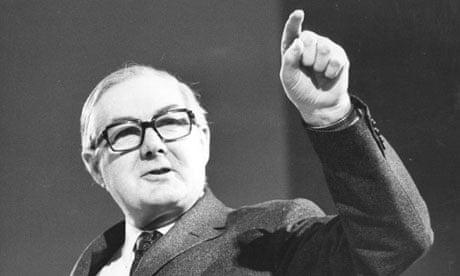

For some, this debate will bring to mind another important period of educational change; the late 1970s, when James Callaghan made his famous Ruskin College speech, which initiated "the great debate" and ultimately led to the national curriculum for England.

Brian Lightman, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, who was at the seminar, is calling for a second "great debate" about education. He wants to see a wide-ranging, inclusive-to-all discussion that would explore education's purpose beyond political expediency and ideology. At the ASCL annual conference, last month, Lightman said: "We need to take stock, look objectively and without political bias at the evidence of what is working and what is not, define and clarify the areas of consensus and set out a vision which will go beyond this and the next parliament."

Those who work in schools may well get behind the idea, especially as so many feel their integrity is compromised by the current system. For example, teachers are not always free to do what they feel is best for students because, as Waters puts it, of "the games they have to play".

Yet, Waters says, there is a lack of resistance from those working in schools: "The crux of much of our present inertia is the influence of national politicians. The teaching profession often acquiesces to the latest ministerial mood swing, complaining rather than being involved," he says. "Schooling needs to act and those in the profession need to see themselves as schooling activists; for example, heads should always respond to consultations, and expect their responses to be taken seriously, or monopolise MPs' surgeries to get their point to ministers." He adds: "Schools should be prohibited as venues for photo opportunities for MPs."

Debra Kidd also believes an "education spring" should come from teachers and parents. "Ofsted rules the roost," she says. "We ask 'what would Ofsted think?' instead of 'what do children need?' It's like we're playing football and running around after the referee and not after the ball."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion