It smells like nirvana. Up here in Madrona, one of Seattle's smartest neighbourhoods, the air from Lake Washington breezes new and sweet. The trees, their leaves shiny, add an extra tang of their own, and what breath you have is taken away by the view. It's the kind of place which makes visitors sigh, "I could live here." No wonder the street signs welcome you to "Madrona - The Peaceable Kingdom".

But one house on the hill has been spoiled. Black plastic tarpaulins hang from the trees to keep out prying eyes, bed-sheets have been pulled across the windows. Nevertheless, you can still see into the room above the detached garage, the room estate agents would call "the mother-in-law apartment".

The patterned lino is visible, so is the bare table, and the vase of pink tulips placed on the floor to mark the exact spot where Kurt Cobain took a shotgun and blew his brains out.

The birds keep singing outside, undisturbed by the police paraphernalia that has cordoned off the driveway since Cobain's body was found. Occasionally a robin comes down to peck at the pools of red candlewax, leftovers from the vigil of fans who gathered here the moment Seattle radio stations declared April 8 the day the music died.

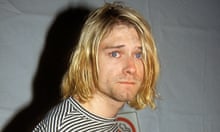

They were mourning the passing of the king of grunge, the frontman of Nirvana whose 1991 hit, Smells Like Teen Spirit, was credited with exporting the Seattle sound worldwide, injecting "indie rock" into the mainstream, and so altering the course of modern music. The grown-up media followed close behind, reporting that Kurt Cobain's death had deprived the world's twentysomethings of a spokesman, that Generation X had lost its crown prince.

To outsiders, the fuss was hard to fathom. For one thing, Nirvana's music is an acquired taste, a blend of punk and metal, in which melody is often buried under layers of sheer noise. And Cobain's story seemed so obvious, so familiar. The words "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" came so easily - and Kurt Cobain's demise had all the elements. From the coma induced by a tranquilliser-and-champagne cocktail in Rome a month earlier (now regarded as a first suicide attempt), to the tales of long-term heroin addiction, to the self-pitying note he left behind - it was a saga of self-destruction that made Cobain look like nothing more than a Nineties Sid Vicious.

But the seven thousand Seattleites who gathered in a memorial service for him - venting their sense of betrayal by chanting a chorus of "Fuck You, Kurt", led by the star's widow, punk singer Courtney Love - felt they had lost something special. "Kurt died for your sins," bellowed one overwrought fan to his fellow mourners. Another showed off the K-U-R-T scar she had razored on to her wrist. There was a ritual burning of flannel shirts, the trademark garment of grunge.

For these people, and for the ten million others who bought Nevermind, Nirvana's blockbuster album, Cobain was a musical original. He was, too, a symbol of his generation and even of his country. But not quite in the way those early obituarists would have you believe. KurtCobain's life and music were much more complex, more riven by tension, than the simple, voice-of-alienated-youth eulogies let on. His 27 years included ironies and confusions that do not fit easily into the conventional Generation X wisdom, but ultimately reflect what it is that distinguishes today's under-30s, and perhaps modern America itself.

This roomy house, complete with skylights and an exterior of grey, wood-slice tiles, is a case in point. Generation X-ers are meant to be the slacker generation, yet here was the slacker-in-chief living the yuppie dream: married, padding around a $ 1.1 million luxury mansion with a garden for his baby daughter to play in, and Microsoft and Boeing executives for neighbours.

It proved to be no refuge for Kurt Cobain, the boy who had come from blue-collar nowhere and made himself an international star and millionaire. Holed up inside the house overlooking the perfume-scented lake, he pumped his veins full of heroin, wrote his rambling suicide note, and did so much damage to his head that police could only identify his body through fingerprints. Dental records were no use, because nothing was left of his mouth.

The neighbourhood will soon be back to normal. No one would ever admit it, but there is probably some relief that there will never again be nights like the one last year when police arrested Cobain after a resident reported hearing the sounds of domestic violence. (He and his wife insisted they were merely jamming and then play-fighting around the house). And no repeat of the March 18 episode - just days after the Rome crisis - when Love called out the emergency services after her husband locked himself in the bathroom with three pistols, a rifle and 25 rounds of ammunition.

Now the house will be quiet. And soon there will only be a trace of irony hanging over the sign, not 50 yards from the Cobain residence, that says "Madrona - drug free zone."

Listening to tonight's line-up at the Crocodile Cafe, grunge's equivalent of the Liverpool Cavern, you realise that Kurt Cobain got lucky. Nirvana once performed at the Crocodile to an audience of six, and they could easily still be here. They did not invent the sound called grunge, but they got the breaks: among them a session on the John Peel show, and the cover of Melody Maker. (Seattle acknowledges that Britain was first to shift the city from the furthest northwestern tip of the US to the centre of the rock universe.)

The punters at the Crocodile, in their punk-hippie hybrid garb of goatees, dungarees, and clothes from Value Village (this area's Oxfam) all say grunge died long before Kurt Cobain. It died when it became big, when the fashion industry got hold of it. Now, they say, they dress the way they do because "we're poor and it rains a lot", and if they occasionally still tie a flannel shirt around their waist, well, that's because it gets cold.

They give equally short shrift to the notion that Cobain was any kind of spokesman for Generation X, or that any such thing exists. "It's just a way to market us," says Teresa de la Rosa, 24. Next to her is Gary Paul, 28, who, despite a college degree is working as a postman - a textbook case of the X syndrome which has overeducated kids working in low-status, low-paid jobs, from office temps to despatch riders. All around him are people in the same position, but he is adamant that there is nothing that unites them. "I think the media are making a big thing of it," he says.

Kurt Cobain would find such talk gratifying. He was utterly disdainful of his own role as the "voice of a generation". Central to his message was a rejection of what he saw as the crude, commercial motive of labelling an age group. The "Teen Spirit" satirised in Cobain's most famous song is a deodorant aimed at young girls.

The fact that Nirvana made millions by appealing to a niche market, partly defined by youth, was an irony not lost on Cobain, who wrote the words and music to all Nirvana's songs, as well as singing and playing the guitar on all of them. The opening lyric of In Utero, the band's last album, was direct: "Teenage angst has paid off well, Now I'm bored and old."

It seems funny, this contract that existed between Kurt Cobain and people like the Crocodile crowd: they deny they are a group, and he denied that he represented them. But one can't fully escape the other. So much of what these kids are about - even if they deny it - was reflected in his short, urgent life.

Take the definitive extract of Cobain poetry, the couplet in Teen Spirit that manages to evoke disillusion, fatalism and inertia in a stroke. "I found it hard, it was hard to find," he croaks, "Oh well, whatever, never mind."

"That was his message, that life is futile," muses 26-year-old Bob Hince, who has completed six years of study in molecular biology but is now heading for Alaska to work as a salmon fisherman. His dyed red hair nearly covers his eyes, falling behind the lenses of his retro, Buddy Holly glasses. He's drinking bloody Marys tonight, and paying no attention to Flake, the band strutting furiously on stage.

"It's just ambivalence. You're at a crossroads, and you don't know what to do," he says. "What am I supposed to be?" Hince says his employment prospects have left him feeling bottled up with anger. "We all are. We all feel the monotony, we all feel we cannot control our circumstances."

And all those feelings are there, in the music. If it's frustration you're after, there's the screaming rage of Cobain's singing, the screech of metallic guitar noise and lyrics like, "Gotta find a way, a better way." Alienation? Try "Stay Away", or the verse which explains, "I'm not like them, but I can pretend." Paralysis? How about Come As You Are, which urges, "Take your time, hurry up." And for sheer pent-up anger, taken neat, there's Tourette's, a hoarse tirade on In Utero. Lyric: "Fuck, shit, piss."

The untrained ear might strain to hear what's new in all this. After all, punk, with its near-identical message, happened a long time ago. Nearly 20 years have passed since the Sex Pistols swore at Bill Grundy, and the Adverts - to name but one - snarled, "It's no time to be 21, To be Anyone."

Kurt Cobain saw this point himself. "I'm the first to admit that we're the Nineties version of Cheap Trick," he said once, and he constantly cited the influence on him of charmingly-named, if little-known British punk bands like the Raincoats and the Vaselines. But punk never made the breakthrough in the US that it did in Britain. The Sex Pistols may have reshaped the pop landscape in the UK, but punk stayed marginal here. "It didn't really catch on," remembers Jeff Gilbert, Seattle-based writer for Guitar World.

The result was a vacuum which Kurt Cobain stepped into effortlessly. "Things had gone soft on us and Nirvana gave it a real boot to the butt," says Gilbert. What Never Mind The Bollocks did for the UK, Nevermind did across the Atlantic.

But Cobain did more than resuscitate punk to rehash perennial themes of teen rebellion. He had an instinctive feel for what made his audience's growing pains different from those of their predecessors. According to Newsweek, "grunge is what happens when children of divorce get their hands on guitars". The one hard item of demographics amid all the guff about Generation X is that, more than any other group in history, they come from broken homes.

"I know only two people whose parents aren't divorced, and one of them - his mother got shot," muses Bob's friend, Mara Rivet, 22, an assistant at Tower Records. She knows that Kurt Cobain's mum and dad, a secretary and a car mechanic, split when he was 10. She's heard him sing, "As my bones grew, they did hurt/They hurt really bad/I tried hard to have a father/But instead I had a Dad."

Bob, Mara and friends understood what Cobain was up to when he jetted off to Hawaii to marry Courtney Love, leader of the band Hole, in 1992. They watched the ceremony (not knowing that Cobain was juiced on heroin at the time), and wished him luck. They had heard the star say he proposed to Love because she was "the best fuck in the world", and they'd seen him show the scratches on his back to prove it, but they identified with another, deeper motive. They knew well that urge to find a home, to belong to a family.

"I was in search of the Brady Bunch, and I didn't find it," smiles Mara, deploying one of the X-ers' favoured cultural touchstones. She ran away after her parents' break-up, and curses Cobain for inflicting a similar, parentless future on the 19-month-old Frances Bean he has left behind. Having seen Cobain's attempt at domestic bliss fail, she is more pessimistic than ever. "There is no Brady Bunch family, goddammit. It's TV, and you're not told."

The cynicism is unsparing. Bereft of the idealism of flower-power, or even the exuberant iconoclasm of punk, grunge is a movement entirely without coherent politics. "There are little things we do, like vegetarianism," says Mara, "but we all know that in the end it'll all be futile."

"There's nothing to believe in anymore," says Mindy Brown, enjoying a night off from looking after her three-year-old daughter. She remembers taking sedatives to calm her fears of a nuclear holocaust. Now she gets her news from MTV. "We all believe there's nothing to believe in."

Kurt was the same way, stumbling only rarely into politics. He occasionally called on his fans to support the rights of women and gays. But he spoke just as often about his passion for guns. He kept an M-16 and 10,000 rounds of ammunition in the hall cupboard, unselfconsciously parroting the right-wing line about the right of Americans to protect themselves.

This is what distinguishes Nirvana and its generation most from the teen rebellions that have come before. Hippies and punks were both public movements, whether they were strumming to stop the Vietnam war or spitting about Anarchy In The UK. Both believed in the possibility of change. But Cobain, like the 20-plussers who listen to him, was private and self-absorbed. "What is wrong with me?" he sang. "I'm so tired, I can't sleep."

He knew this introspection was unattractive, once describing his public image as a "pissy, complaining, freaked-out schizophrenic who wants to kill himself all the time." But that only made him loathe himself more. In this, he was a Generation X exemplar. "We're spoilt, rotten brats," says Mindy. "Slap Us!"

Typically, Cobain's suicide note, read by Courtney Love to the thousands at the Seattle service, did not complain about Aids or divorce or homelessness or any of the other things said to be preoccupying the post-1965 generation. It talked about the chronic stomach condition which Cobain always said impelled him to use heroin, "to medicate himself".

"I thank you," he wrote, "from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach …" It was somehow a perfectly apt ailment. For one thing, it proved that Cobain's pain was no affectation: he felt it deep in his gut. But it was also grimly appropriate that the boy-prince of the brat generation should die complaining of a tummy ache.

"Our parents built up this sense of expectation, and we can't live up to it," whines Bob Hince about his economic future. Cobain reflected even this, the ugliest of Generation X's traits: its passivity, its self-pitying feeling of entitlement, its expectation that mummy and daddy owe them a future.

Cobain was smart enough to send up the sentiment. "Here we are now, entertain us," he wailed in Teen Spirit. And his grieving widow, reading his suicide note to the fans, was able to show similar contempt. When she came to the passage in which Cobain moaned that he was a "sad, little, sensitive Pisces-Jesus man", she stopped reading and yelled at the ghost of her dead husband, "Oh, shut up!"

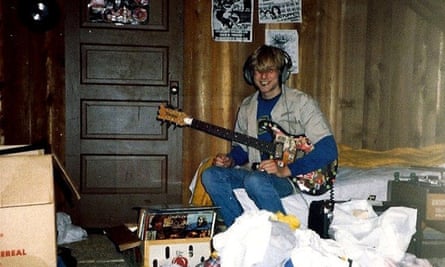

Aberdeen, Washington is not yet a shrine, but it may become one soon. Already, graffiti adorns the wall of a burnt-out restaurant: Kurt Cobain RIP. This shabby, peeling town of 16,000 lumbermen, loggers and fisherman, was where the frail, blue-eyed blond with a penchant for drawing and poetry grew up. The 100-mile road between here and Seattle is full of lorries packed with tree-trunks, stacked like cigarettes. There is timber everywhere, firs and pines scraping the sky like sharp pencils, and cut into tiles on the houses - including the neat, green one where Kurt Cobain's mother still lives.

Her son was born in February 1967, and, he said later, he was happy for seven years after that. (In his farewell letter, he wrote that he had felt "hateful toward all humans in general" from age seven onwards). His parents divorced when he was eight, and he didn't speak to his father until he started making hit records.

After the divorce, the child turned inward. The teachers at Aberdeen High School remember him as withdrawn, someone the other kids would avoid. "When I had him in class, the anger was definitely there," recalls Bob Hunter, a soft-spoken art teacher whose classes Cobainmade a point of attending. (He bunked off most of the others, only to sneak back into the library.)

Surveying his art-room, Hunter points out Kurt's seat, close to his own. A rock station is playing on the radio, just as it would have done then. Cobain used to offer a song-by-song critique of whatever came on, usually "pretty sarcastic", says Hunter. The teacher held on to oneCobain effort which he thought showed exceptional "originality, creativity and sophistication". It was a pencil drawing that showed, in 12 stages, the transformation of a sperm into a foetus.

Ironically, given his ultimate fate, Cobain seems to have been far more obsessed with birth than death. Several hired cleaners fled his Seattle home after they spotted his collection of model foetuses, bought from a medical supplies manufacturer. He used the smashed remnants of some of them to assemble a collage for the sleeve of In Utero - which led the Wal-Mart store chain to ban the record.

Cobain was bored by school and dropped out, passing up an art school scholarship. He became a janitor at the YMCA, living with the family of another Aberdeen High teacher, LaMont Schillinger, whose sons were friends of his. Cobain came to stay for a few days, after a row with his mother's boyfriend. He ended up rooming there for a year.

"I think Kurt was a kid that nobody ever got to know," says Mr Schillinger now. Cobain later told a biographer that he began shooting up heroin while he stayed at the Schillingers', but the head of the household thinks his former lodger made the story up, mischievously seeking to inflate his own rock 'n' roll myth.

The boy LaMont Schillinger remembers took his turn cooking, cleaning, chopping wood. He may have also been running around town spray-painting "Abort Christ" on born again Christians' pick-up trucks, but at the Schillinger table he sat quietly, even during grace.

The teacher's pupils have been asking about the suicide, accusing Kurt Cobain of an act of gross selfishness. "He was an inward-directed person," Mr Schillinger has been telling them. "I don't think there was a choice."

At Rosevear's music store, the only one in town, Kurt Cobain's spirit was always in the air, even before he died. Manager Les Blue, a music enthusiast with Wayne's World looks, had thought of putting up a No Nirvana sign - to deter the legions of wannabe guitarists who all try out the merchandise the same way, playing the intro to Smells Like Teen Spirit.

Blue has strong memories of Aberdeen's most famous son, from the days when he, Blue, managed the local drive-in. "He graffitied the hell out of my bathroom," he says. In red marker, Cobain wrote HEROIN next to a picture of a syringe, and the words SID AND NANCY.

He heard Nirvana play before they were Nirvana - when they were Pen Cap Chew; Ted, Ed, Fred and Skid Row. "They kinda sucked," he recalls.

Their eventual success was, says Blue, an inspiration to Aberdeen, a town depressed by cutbacks in the logging industry, forced by environmental regulations. "People thought, 'If they can do it, anybody can do it."' A cassette of Blue's own band is on sale at the counter, just in case.

There is an irony in this late embrace of Kurt Cobain by the people of his hometown. It takes only a brief visit to the local music venue to see how miserable a time he would have had fitting in here.

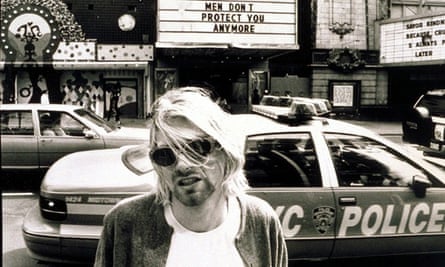

In Aberdeen, which even now has Wild West-style saloons and card rooms, new bands cut their teeth at the Pour House, a wooden tavern where the men wear tattoos and mean it. This must have been a harsh training for the waif-like performer, who, once in liberal Seattle, was fond of donning his wife's cotton dresses, lining his eyes, and painting his nails a lurid red.

Many in Cobain's position would have gloated as Nirvana's success turned many of the redneck jocks who had made a sport of beating up young Kurt into loyal fans. But it gave the singer no pleasure. The chorus of In Bloom was a musical jeer at the band's new audience: "He's the one who likes all our pretty songs, and he likes to sing along, and he likes to shoot his gun, but he don't know what it means," sneered Cobain.

It twisted his stomach to think that he was providing a soundtrack to the lives of those he despised. When he learned that his song, Polly, an ironic essay with a rapist-narrator, had been used as musical accompaniment to a real-life gang rape, he was horrified. On the sleeve notes for his Incesticide album, he issued a plea: "If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different colour, or women, please - leave us the fuck alone."

The fact that Nirvana struck a chord not only with Generation X, but with a large swathe of blue-collar white, male America - men with despair and alienation of their own - was just one of dozens of problems Kurt Cobain had with success. For a champion of the punk ethic of anti-commercialism, multi-million record sales were a confusion. And intrusion by the press into his private life was insupportable for a man who had been a loner since childhood. "It was so fast and explosive," he said once, "I didn't know how to deal with it. If there was a rock star course, I would have liked to take it. It might have helped me."

The life that suddenly became possible for Kurt Cobain was riddled with contradiction. The layabout rock-star now lived in a Seattle suburb with a little girl, a working wife, and a home in the country. He was feeding a heroin habit that was draining $ 400 a day (the largest daily dose dispensed by his cash-machine), driving to his dealer in a Volvo.

You could hear the pop junkie and the doting dad fighting it out in the music. On Nirvana records, din and harmony alternate within a single song, sometimes at the same moment. Last year Cobain clashed with the producer of In Utero, who wanted a harder, less commercial sound for the album. Cobain triumphed, and you can hear the melodies, many of them Squeeze- or even Beatles-esque, struggling to break through the sheet metal on top. He promised that future work would be more tuneful, acoustic - even ethereal.

Hippies, punks and every other teen movement in history would have taken this Volvo-driven volte-face as a sell-out. But not the twentysomethings, the children of Reagan and Thatcher who have shed politics and who came of age in the consumerist 1980s. X-ers don't have a problem with the system - they just can't find their place in it.

They cheered as Cobain seemed to find his. And this is the strangest irony of all. Sceptics have rightly debunked the Generation X idea for failing to account for all those in their mid-20s who are not working in McJobs, but married and high-achieving. These Xuppies probably outnumber the slackers five to one - yet the bizarre fortune of Kurt Cobain was that, by his success, he reflected them, too.

That's why stock analysts listened to Nirvana on their car CDs. His disenchantment with success-without-meaning - singing, "I do not want what I have got" - spoke to them, too. Douglas Coupland's novel, which dumped the Generation X moniker into the language, coined another new term: Successophobia. He defined it as "The fear that if one is successful, then one's personal needs will be forgotten".

Cobain had a bad case of successophobia. "I just hope," he said in January, "that I don't become so blissful I become boring." One of his best chorus lines was, "I miss the comfort of being sad."

He coped by mixing his blood with the soothing nectar of heroin, but its healing power could not last. He had wanted to call his last album, I Hate Myself And I Want To Die. He decided not to because, he said, no one would realise he was joking.

Looking at the house on Lake Washington Boulevard, with its space, its quiet, its pure aroma, you feel about Kurt Cobain the way nations around the world often feel about America: why are those who have so much so desperately unhappy? Kurt Cobain's anguish might have been just as poisonous, just as lethal had it remained anonymous. He took his own life for private reasons - it has been reported that his family had a history of suicide - even if those reasons were magnified by the lens of fame. And, in the end, the greatest impact of his death will be private, too.

It is now late afternoon, and a black limousine has turned into the driveway. A pale Courtney Love steps out, her platinum hair looking lank, hugging herself in a plain, grey tunic. She clutches a copy of Newsweek, the one which shows a staring picture of her dead husband.

She heads immediately for the garage-apartment, getting closer to the spot where Kurt Cobain's body lay for three days before it was discovered. She doesn't see the nanny coming out to greet her, cradling the couple's newly-bereaved baby daughter. For Courtney Love is looking the other way, shouting simply, "Where are you?"