Social mobility is in the news today. The Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, will announce publication of 17 data-led indicators showing how mobile we are as a society.

Social mobility is the kind of thing all politicians can sign up to: it's the idea that it doesn't matter where you come from, you should have the same chances to progress.

The government says it will publish indicators including:

School readiness – the proportion of children on free school meals achieving a 'good level of development' in the Early Years Foundation stage compared to other children.

Attainment at ages 16 by free school meal eligibility – the proportion of children achieving grades A* to C in English and Maths at GCSE.

18-24 participation in education by social background – participation in full-time education by social background.

High attainment at age 19 by school or college type – proportion of children studying towards A-level qualifications at age 17 achieving at least grades AAB at A-level in subjects identified by the Russell Group as 'facilitating' entry to their universities - by types of school or college attended.

So, how socially mobile is Britain today? We've collected the key data together which shows that, as far as social mobility goes, the UK is way behind many other countries. There is already a lot of data out there on this - in particular the OECD's recent report on social mobility across the world and a recent report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on social mobility.

Here's what the figures show:

Britain has some of the lowest social mobility in the developed world - the OECD figures show our earnings in the UK are more likely to reflect our fathers' than any other country

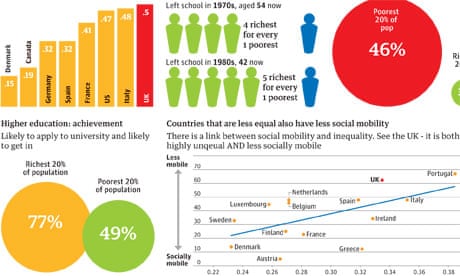

Social mobility hasn't changed since the 1970s - and in some ways has got worse. For every one person born in the 1970s in the poorest fifth of society and going to university, there would be four undergrads from the top fifth of society. But if you were born in the 1980s, there would be five

24% of vice-chancellors, 32% of MPs, 51% of top Medics, 54% of FTSE-100 chief execs, 54% of top journalists, 70% of High Court judges …went to private school, though only 7% of the population do

Education is an engine of social mobility. But achievement is not balanced fairly - for the poorest fifth in society, 46% have mothers with no qualifications at all. For the richest, it's only 3%

Parental influence still makes a big difference to a child's education in the UK, especially compared to other countries - in fact in the UK the influence of your parents is as important as the quality of the school - unlike Germany, say, where the school has a much bigger role

Higher education is not evenly balanced either in terms of aspirations - 81% of the richest fifth of the population think their child will go to university, compared to 53% of the poorest

… or achievment: 49% of the poorest will apply to university and get in, compared to 77% of the richest

There is a strong link between a lack of social mobility and inequality - and the UK has both. Only Portugal is more unequal with less social mobility

If you are at the top, the rewards are high - the top 1% of the UK population has a greater share of national income than at any time since the 1930s

Our findings reflect work in the area by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which has found

We also know that about half of this intergenerational transmission of income occurs through education: cognitive skills measured using standardised tests, which are highly rewarded in the labour market and are not evenly achieved by children from more or less affluent families. These cognitive skills (education) will be an important part of intergenerational inequality persisting across generations in highly unequal societies such as Britain, both because of these social gradients in acquiring them and in terms of how well they are rewarded. So to put it another way the issue of economic opportunity for children both reflects who gets the best jobs and how much more these jobs pay

We've extracted the OECD data below for you to download - what do you think it shows and what can you do with it?

Download the data

DATA: download the full spreadsheet

NEW! Buy our book

Facts are Sacred: the power of data (on Kindle)

More open data

Data journalism and data visualisations from the Guardian

World government data

Search the world's government data with our gateway

Development and aid data

Search the world's global development data with our gateway

Can you do something with this data?

Flickr Please post your visualisations and mash-ups on our Flickr group

Contact us at data@guardian.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion