Would you eat a jellyfish? The most likely answer would be “no; they look disgusting. And they’re probably poisonous. Shall I wash it down with a nice glass of chilled urine?” But, inevitably, some people do eat them. They might even enjoy them, the maniacs.

But Cnidaria cookery methods aside, consider this; would it be OK for a vegetarian to eat jellyfish? If not, why not?

A lot of people are adopting a vegan diet this January, and more power to them. Their motivations may vary (for charity, for the health benefits etc.) but it’s still a big wrench, to remove a vast swathe of choice from your daily diet.

To clarify, I’m not vegan myself, or vegetarian. I do like meat, and I simply lack the willpower to cut myself off from it entirely. As a result, I have a lot of respect for those who do manage it. But as anyone who’s heard the phrase “I’m a vegetarian, except for fish” will have realised, there are different levels of commitment to vegetarianism, and people differ wildly on what they consider acceptable or not.

Part of this may stem from the differing motivations for being vegetarian/vegan in the first place. Some do it for religious reasons, so what you eat is determined by your holy text or scripture etc. Restrictive perhaps, but at least you know where you stand. Other people simply don’t like meat, or are intolerant to it or other animal products, so just avoid them altogether. In this case, it’s your immune system that determines your diet.

There are also sound environmental reasons. While there are concerns over the environmental impacts of popular vegetarian-friendly substances like palm oil, the environmental cost of meat production is undeniable, and staggering.

But many people adopt vegetarianism/veganism for moral and ethical reasons, which is fair enough. Objecting to animals being killed or suffering for our food is a perfectly logical stance. But when you get down to the actual scientific minutiae of what these things mean, then it starts to get confusing.

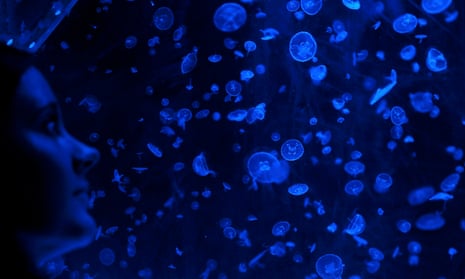

This brings us back to the jellyfish question; would it be safe for a vegetarian to eat one? If you’re vegetarian for environmental reasons, it may even be better to eat jellyfish, given how abundant they are without any need for harmful human cultivation. But what about ethical concerns? While technically classed as “animals”, they are devoid of any brain or nervous system, and most can’t even control where they move. Everything we know about neuroscience suggests such a creature would be totally incapable of perceiving anything as complex as suffering or discomfort, and it certainly wouldn’t be able to experience any emotional reaction to such an experience. So by eating one, no suffering can be said to have occurred. It may still be a living thing, but then so is a carrot. Why is one OK to eat and not the other?

The ability to perceive and demonstrate discomfort and pain does seem to be a big factor in whether a species is deemed a valid part of one’s diet. A very interesting discussion can be found on Richard Herring’s excellent Leicester Square Theatre Podcast with comedian and vegan Michael Legge, about whether honey is vegan. Legge insists that it isn’t because it’s a substance made by animals, which is a perfectly logical (and consistent) argument. However, you can also see why some might think it’s OK. Removing honey from a hive generally does no harm to the bees, apart from maybe annoying them. Bees are another confusing one. They make honey anyway, it’s not something humans force them to do, and they make way too much so us taking some isn’t harmful.

Insects and vegetarianism have complex relationships. Many argue that vegetarians should eat insects, for environmental and ethical reasons. Insects are incredibly easy to produce and contain ample nutrients, and insects also aren’t cognitively complex enough to process things like suffering and discomfort. However, that’s individual insects. Species like the aforementioned bees form large colonies, and many consider these “superorganisms” the true manifestations of insect intelligence. So is it ethically wrong to harm these? I can’t tell you that.

Insects, jellyfish and other species probably seem fair game to many due to a simple failure of empathy. Big, furry or fluffy creatures we can relate to, “ugly” or different ones make it harder, so concern for their wellbeing isn’t so common, unfortunately.

This sort of dilemma, regarding what’s ethically acceptable to eat, is likely to get more complex as food production technology advances to meet demands. Already, humans are too widespread for modern methods to be 100% animal friendly (modern harvesting methods inevitably kill or displace many creatures while gathering vegetable crops) and our species will need increasing volumes of food as time passes. Technology will hopefully provide solutions to this, but also muddy the waters further.

Stem cell meat is one big hope for the future, allowing meat to be grown and produced in the lab, rather than the abattoir. But are they vegetarian safe? If an individual burger is grown from a clump of stem cells, then no animal has been harmed in its production. But if those stem cells were originally taken from a slaughtered animal, is it still ethically wrong? Yes, to begin with, but what if it’s the same stem cell line being used 20 years later, preventing other animals from being used? Is it still bad then?

Maybe we’ll end up working out how to recycle food with great efficiency. Given that we can now 3D-print human tissue, it’s not too far-fetched to predict a time when we can easily print food. Imagine a technical system where you throw wasted or unwanted food in one end, it’s broken down into its constituent molecules (fats, proteins, sugars), these are fed into a printer link specific ink from dedicated cartridges, and they’re reassembled as fresh, recognisable foodstuffs. That would be very useful, no doubt.

But what if you poured a load of half-eaten burgers in one end and used their mass to produce vegetables? Would they be safe for vegans to eat? It might not look like it, but the original meat matter is completely broken down and reassembled, exactly as it would be if you put the burgers in a compost heap and used them to grow tomatoes. That would be acceptable, why not this? It’s just a faster, more technical version of the natural processes that sustain us. Possibly a more environmentally friendly one? You just know people will object though, because that’s what we do.

There aren’t any obvious solutions to any of this, it’s just interesting to note that, when you apply detailed scientific analysis, the divide between vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism is a lot more blurry than you’d expect. It’s the same with race.

However, if in 10 years you’re sitting down to a box of Jellyfish nuggets, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Dean Burnett regrets sitting down to write this so close to lunchtime. He’s on Twitter, @garwboy

The Idiot Brain by Dean Burnett (Guardian Faber, £12.99). To order a copy for £7.99, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min. p&p of £1.99.

class=�vsE1�

.8 Coo��v7�1�

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion