A NEW TAKE ON GRACE

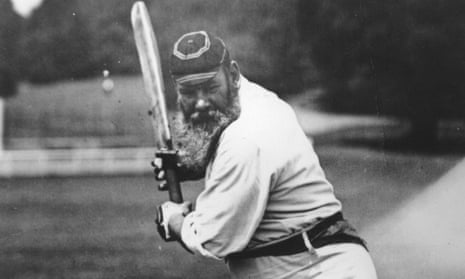

Hard to believe it’s him. He looks so unlikely. Battered white hat, sleeves rolled, trousers tugged high and of course that great salt and pepper beard, hanging down to his chest. He sets himself in front of a single stump. Back foot parallel to the crease, front foot angled both out at 45 degrees and up, cocked. As the bowler approaches he lowers it down, moving his weight from the heel to the toe. At the same time he brings the bat up, waggles it once in mid-air, then lofts it again, to the top of his backlift. Six balls, that’s all. And soft ones, intended only to give the batsman the best chance to show off his shots.

And so he does. Three easy drives to the on-side, another to the off, two glances towards mid-wicket. He’s defending a single stump, there, really, only for orientation. Behind him, a small crowd, which hardly seems to move. Look closely, however, and you’ll see one old man lean out from around another to catch a good look, and a small boy snap his head around in excitement and talk to his friend. Then the camera cuts and the batsman is gone. That’s it, all the footage we have of one of the greatest, perhaps the very greatest, careers in English sport. The Champion, the Doctor, the Grand Old Man. WG. It gives us the beginnings of an idea about his style – but no more than that.

This month marks the 150th anniversary of Grace’s first-class debut, which falls on Monday 22 June, for the Gentlemen of the South against the Players of the South. He was 16. This year also marks the 100th anniversary of his death, on 23 October 1915. He was 67 and had been playing as recently as the year before, his final innings an undefeated 69 out of Eltham’s total of 155 for six against Grove Park. His career as a competitive cricketer spanned six decades and, most likely, he played more innings and scored more runs across all levels of the game than anyone else in history.

A rough sum that, since hard numbers are impossible to come by. But there were 870 first-class matches, for sure, which puts him third to Wilfred Rhodes and Frank Woolley, and countless more that didn’t carry that status. For 50 years, he bestrode what was then the national game, much as Nelson looks down on London from his column, leaving the best of his contemporaries like Landseer’s bronze lions, lying beneath his feet. Certainly Donald Bradman is the only cricketer who could be said to have made anything like such an impact on the public consciousness.

We are still writing about Grace now, still reading about him, still learning about him. There have been three major biographies of him in the last 15 years alone. This summer, BBC Radio Bristol are running a series of documentaries on him. And yet, somehow, the more detail we uncover, the more the man himself seems to recede from view. The more we learn, the less we understand.

There are too many contradictions. Grace was the champion of the sport and yet also “a shameless cheat” as Geoffrey Moorhouse wrote in Wisden. (“They’ve come to see me bat,” and all that). Grace was the supreme cricketer, “an all-round athlete of the highest calibre”, according to Simon Rae. And he was also a roly-poly figure, almost 15 stone as a teenage and 22 stone as an adult. Grace was an amateur and he earned more from the game than any professional of his era. It is hard to knit together what we know.

And so to a rather brilliant new novella by Charlie Connelly, called, quite simply, Gilbert. Because, as the blurb says, “to the public he was The Doctor, The Champion and WG, but to those who knew him best he was simply Gilbert.” Gilbert is an intimate portrait, slim and sparely written but full of detail. It takes us through the final years of Grace’s life, from 1898 to 1915. It begins with the famous story about his being dismissed three times in three balls by Charles Kortright, the first leg before, and the second caught behind. Grace stood his ground. The third, of course, bowled him. And so Kortright offered the send-off: “Surely you’re not leaving us, Doctor? There’s one stump still standing.”

As Connelly imagines it: “Grace paused briefly as if he was about to turn and respond but instead marched off at a quickened pace, announcing to the waiting members as he strode up the steps that he had never been so insulted in his life.” You know the stories but you’ve never heard them told quite like this.

Connelly explains his game in an entertaining early chapter that captures a conversation between Grace and his ghost writer, Arthur Porritt. Poritt hopes to write a book that will “look behind the curtain of the public face and share the real man with the reading public”, but finds himself frustrated by Grace’s incomprehension that there is anything to explore beyond the “bare facts of his achievements”.

“I think your readers would very much enjoy any insight you can give them into what the experience actually felt like. People want to put themselves in the place of WG Grace as he was making that 100th century, what thoughts were in his mind, what the whole experience of such a big innings and extraordinary landmark means to WG Grace as a man and a batsman.”

Grace was silent for a few moments.

“I want to help you, Porritt, truly I do,” he said, “but to be perfectly honest with you I did not feel anything. I had too much to do watching the bowling and seeing how the fieldsmen were moved about to think anything. It’s as simple as that.”

The facts lack. Connelly has taken that gap in our understanding of Grace and filled it from the well of his own imagination. He shows us the Grace who gave away his wicket so he could skip away from a match to take his very first ride in a motor car; the Grace who would stand in his garden and shake his fist at the Zeppelins flying overhead; the Grace who had to bury his daughter and his eldest son, both parents, and both brothers.

What emerges is a portrait of a man who lived for the moment when the ball leaves the bowler’s hand and “absolutely nothing mattered other than his duel with it. The years fell away, the occasion melted to nothing and there was just him and the ball, locked in a duel”. It is a wonderful book, and though it’s a fiction, it brings us closer to an understanding of the man than any number of facts or any amount of film footage.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion