The country is fractious and disunited. The heir to the throne frets impatiently, lacking a visible public role. The monarch is a strangely isolated figure better at public duties than private relationships. Such might be a rough outline of the two parts of Shakespeare's Henry IV. But, whatever the fortuitous topicalities, the strength of these monumental plays lies in their comprehensive portrait of England and their mythic vision of the contest between pragmatism and charity. They are, in every sense, England's national epic.

It is fascinating how they have always been used as a national symbol, more than any of the tragedies or comedies. In 1932, they were chosen to open Elizabeth Scott's new art deco Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. In 1945, they were part of the legendary Olivier-Richardson Old Vic seasons at the New Theatre and seemed to embody that sense of deep England for which people had fought a long and exhausting war. In 1951, Festival of Britain year, they were the centrepiece of a Shakespeare history cycle at Stratford and catapulted their brooding Prince Hal, a young Richard Burton, to international fame.

Now the plays are due to be revived by Nicholas Hytner at the National Theatre; and clearly they are part of Hytner's ongoing plan to use its three stages to explore England's national and cultural identity. But when we talk of the essential "Englishness" of the two parts of Henry IV what is it we mean? One obvious answer is that no plays in our literature offer a more panoramic picture of the nation. They embrace Scotland and Wales but, geographically, their heart is in England as they move rapidly and easily between the Westminster court, Eastcheap taverns, border battlefields and the Gloucestershire and Kent countryside. Shakespeare invented a whole genre in which history became a way of not merely chronicling great events but of analysing a nation's soul.

But for me this famed "Englishness" rests in something else: a proximity to real life and a mixing of the momentous and the mundane that runs through all our literature. That native genius for realism animates every scene of Henry IV. After the heraldic formality of Richard II, Shakespeare seems determined to show us what England is like at every social level. Just before the Gadshill robbery, there is an extraordinary scene in a Rochester inn-yard. Two carriers complain of the filthy conditions of the inn: "why, they will ne'er allow us a jordan [chamber-pot] and then we leak in your chimney, and your chamber-lye [urine] breeds fleas like a loach." Dramatically, you could say the whole exchange is superfluous; but it seems part of Shakespeare's subconscious desire to investigate the whole nation that he takes time to include a scene about unsanitary inns and the way pissing in chimneys breeds vermin.

Shakespeare's technique of mass observation is most famously present in the Gloucestershire orchard scenes where Falstaff visits Justice Shallow. The scenes are necessary in that they reveal Falstaff's predatoriness and provide a build-up to his rejection by the newly crowned Hal. But Shakespeare goes beyond the demands of narrative in capturing the mental fluctuations of old age. You have only to listen to Justice Shallow: "Death, as the Psalmist saith, is certain to all; all shall die. How a good yoke of bullocks at Stamford fair?" Shallow leaps from the subject of mortality to the price of cattle in Lincolnshire. This is not just how old people talk: it is realism raised to the level of poetry in that death, decay and the ravages of time provide the leitmotif to the whole elegiac tapestry of Henry IV Part Two.

But if Henry IV Parts One and Two constitute England's national epic, it is not just because of their native realism. It is also because the two plays embody, in the persons of Prince Hal and Falstaff, contrasting philosophies and attitudes to life. And, although it is easy to say that everyone loves Falstaff and hates Hal, I would argue that the moral complexity of the plays depends upon our acknowledging Hal's necessary virtues and Falstaff's often overlooked vices.

The case against Hal is familiar: that he announces early on that he is cultivating his wastrel image, and the company of Falstaff and his low-life companions, in order to make his later reformation all the more startling. As Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch once wrote, youthful hot-blood and riot are forgivable but "a prig of a rake is something all honest men abhor". But the plays subvert Hal's stratagem in that they show Falstaff becoming a necessary surrogate father to the emotion-starved prince. And, whatever the cruelty of Hal's public rejection of Falstaff, it can also be viewed as something that costs the king dear.

As for Falstaff, there are as many ways of looking at him as there are commentators. To the idolatrous Harold Bloom, he is a "comic Socrates" and a life-affirming vitalist of the order of Chaucer's Wife of Bath, Cervantes's Sancho Panza and Rabelais's Panurge. WH Auden also saw him as a Christian symbol representing "the supernatural order of charity". Most intriguing of all is the view of Jonathan Bate who seizes on the little-observed fact that Falstaff began his career as page to Thomas Mowbray, Duke of Norfolk: a name associated in England with Catholicism. Bate deduces that Falstaff's journey into deep England is therefore "a journey into the old religion of Shakespeare's father and maternal grandfather". In rejecting Falstaff, the Protestant-Puritan Henry V may even be undergoing a religious "reformation" and turning away England's former Catholic self.

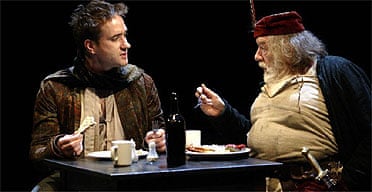

What all these downplay is Falstaff's extraordinary mixture of qualities: his cynicism and cruelty as well as his overflowing wit and companionability. In Adrian Noble's 1991 RSC production, Robert Stephens' Falstaff was a figure of infinite jest and a man who worshipped Hal as a son. But Stephens showed in Falstaff's dimissal of his ragged battle-recruits as "food for powder" a casual contempt for human life. And his treatment of his old Inn of Court contemporary, Justice Shallow, as no more than "bait for the old pike" - a word Stephens seized upon - put in context Falstaff's own later rejection. To treat Falstaff as a Christian symbol is to show a very strange view of religion and to rob him of his infinite complexity.

It also weakens the moral and dramatic impact. Shakespeare is offering not only an unmatched portrait of England. He is writing, as so often in the histories, about the cost of kingship and the price of power. Hal, to become an effective ruler, has to overcome the chivalric glamour of Hotspur and renounce the seductive companionship of Falstaff. If it is simply a story of a dessicated calculating-machine who rejects a lovable rogue, it is predictable and un-interesting. But if one sees the two plays as a study in the painful solitude of power, then they acquire a universal resonance. They also confirm my long-growing suspicion that Shakespeare speaks most clearly to us today through his history plays. We share the suffering of Hamlet and Lear. We mingle tears and laughter in our response to Shakespeare's sublimely melancholy comedies. But it is in the histories that Shakespeare, in a way unmatched elsewhere in drama, explores the national psyche, analyses the dynamics of power and effortlessly combines reality and myth.

· Henry IV Parts One and Two is at the National Theatre, London SE1, from May 11. Box office: 020-7452 3000.