"It's funny, you don't look like an otaku."

I wrinkled my brow and laughed. "That's because I'm not an otaku," I shot back.

"No, you definitely are!"

This was the end of a discussion I had with my Japanese coworker. I had commented on a Dragon Ball figure on his desk. Pretty soon we were talking about old manga. Mildly nerdy at best. Definitely not otaku territory. Or at least that's what I kept telling myself.

I don't cosplay. I don't go to conventions. I don't obsess over cat ears, maid outfits, or tsundere characters. Nor do I shun sunlight and social interaction. The "O-word" should be reserved for the nerd elite. Not a healthy sun-and-people-and-okay-maybe-Dragon-Ball-loving adult such as myself.

But by the end of that day, I was questioning my idea of the "otaku meaning". Worthy or not, I had been labeled by my coworker.

I decided to prove him wrong. Or at least come to terms with who and what I was. This led to months of reading and research about Japanese nerd culture. But in the end, I was indeed able to answer my question:

"Am I otaku?"

The History of Otaku

Before answering that, it's important to understand the history of otaku. When researching the word and subculture, one thing becomes clear: the meaning of "otaku" is riddled with ambiguities. Its definition depends on who's defining it. Media and cultural trends have shaped the term's popular perception over time.

To understand otaku, we have to understand where it came from and how it evolved.

An Alternative to Reality

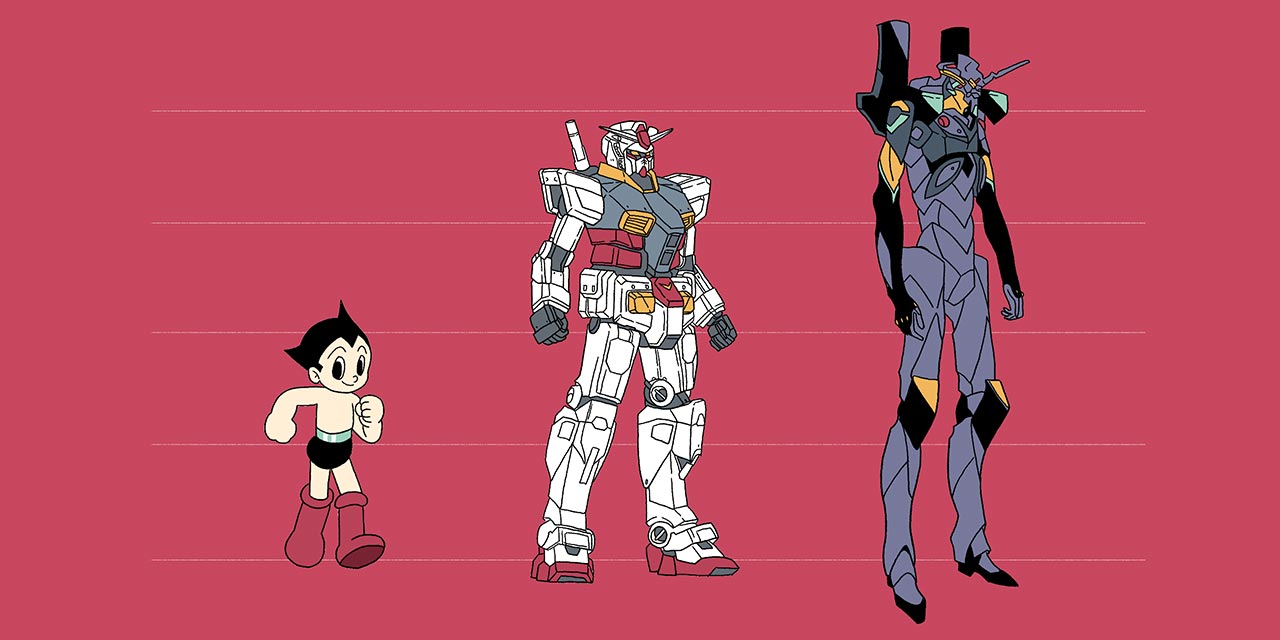

Before the word "otaku," there were people who were interested in manga and anime. Osamu Tezuka's dynamic stories and appealing characters set the wheels in motion. Astro Boy and Princess Knight added deep narratives never seen in manga before. All these and more created passionate fanbases.

During this era, disposable incomes, along with TVs and VCRs, were on the rise. This gave anime a national audience. The new medium became a marketing force throughout the 1980s with Space Battleship Yamato, Mobile Suit Gundam, and other hits.

Disenfranchisement further fueled anime's growth. The youth protests of the 1960s and the economic bubble burst of the late 1980s were harsh realities.

Disenfranchisement further fueled anime's growth. The youth protests of the 1960s and the economic bubble burst of the late 1980s were difficult times. Manga and anime provided a form of escape. The overworked, underpaid, and unemployed found comfort in their fictional worlds.

I couldn't help but relate to this. Weekly episodes of anime I enjoy give me something to look forward to after a hard day's work. One point for "I'm an otaku."

The Origin of the Word "Otaku"

As the manga and anime industries grew, the fandom looked for ways to connect. The 1980s saw a boom in conventions, college clubs, and the overall consumer base. Suddenly there were social events fueled by fictional universes.

Shared interests gave these strangers common ground. But the Japanese language offered no concrete way for unacquainted fans to casually (but not too casually) refer to each other. Famed social critic and anthropologist Eiji Otsuka recalls,

The problem is that in Japan, there isn't a proper word to express you in a situation where you want to speak passionately and personally about something to… someone whose name you don't know, and to whom you haven't been introduced formally. Calling the person by the second-person pronoun anata would sound strange as this is a word used between married couples. There is another second-person pronoun, kimi, but the relationship suggested by the term is too intimate. As a result, fans used the term otaku, which is a sort of honorific, somewhat ambiguous second-person pronoun.

Though the word "otaku" grew semi-organically, one man popularized it within the Japanese nerd crowd. Nakamori Akio, a writer critical of the developing subculture, used the term to describe convention-goers in an article for Manga Burikko magazine in 1983. The rest is history.

- オタク(おたく)

- geek; nerd; enthusiast

The boys were all either skin and bones as if borderline malnourished, or squealing piggies with faces so chubby the arms of their silver-plated eyeglasses were in danger of disappearing into the sides of their brow; all of the girls sported bobbed hair and most were overweight, their tubby, tree-like legs stuffed into long white socks. Now these unassuming classroom corner-dwellers with their perpetually downcast expressions have come out of the woodwork and swelled their ranks into a really rather surprising TEN THOUSAND PEOPLE… For whatever reason, it seems like a single umbrella term that covers these people, or the general phenomenon, hasn't been formally established. So we've decided to designate them as the "otaku," and that's what we'll be calling them from now on.

Although Nakamori's infamous name labeled the fandom, it was contained within the subculture. It took a famous crime to catapult the term "otaku" into the public consciousness. Suddenly, calling myself otaku seemed much less appealing.

The Otaku Murderer

From 1988 to 1989, a man named Tsutomu Miyazaki murdered four young girls in Saitama. His crimes included cannibalism, necrophilia, and vampirism. He even went as far as to preserve body parts as trophies. But despite the bizarre nature of these killings, the media focused on one thing: he had a large collection of anime and manga.

Japanese anthropologist Eiji Otsuka recalls the incident,

News reports on Miyazaki described him not just as a serial killer, but also as an otaku, and this was what really brought the term to the public and shaped perceptions of it. The media implied that Miyazaki committed the crime because he couldn't tell the difference between reality and fiction.

But was Miyazaki a true otaku? Otsuka contends that Miyazaki's media collection lacked the focus required to earn him the otaku name. But others felt his anime filled apartment justified the label. Furthermore, his participation in fanzines and conventions warranted the media's conclusion.

True otaku or not, few sources mention Miyazaki's troubled past, nor the cannibalism, necrophilia, and mutilation that took place. To me, these disturbing details separate Miyazaki from other murder cases and suggest his mental health played a role in the crimes.

Still, the media spun the murder case into a social issue: otaku were the problem. Otaku historian Roland Kelts explains, "The Japanese media branded Miyazaki 'The Otaku Murderer' and people who had never before heard the term 'otaku' came to know its pejorative meaning very well."

The media frenzy surrounding the murders twisted "otaku," giving the term a dark connotation. The murder case became a social issue, and otaku were the problem.

The media frenzy surrounding the murders twisted "otaku," giving the term a dark connotation. This reaction reminds me of the way Western media blamed the 1999 Columbine High School massacre on video games and industrial music, painting the "goth" subculture as sinister.

Even as the fervor over the Miyazaki case died down, otaku's negative stigma remained. To the general public, the group came to represent men who preferred an imaginary world over reality and had trouble differentiating between the two. These fanatics abandoned marriage, family, and health to invest themselves in a "valueless" hobby.

The Antisocial Myth

Miyazaki's lifestyle, including his dark "otaku room," antisocial tendencies, and "disturbing obsessions" came to embody the otaku stereotype. Otaku became as synonymous with hikikomori (shut-ins) as they are with anime and manga. The subculture's reliance on television, computers, and the internet fueled this antisocial mythology.

- ものコミ

- "thing" communication

This was more along the lines of my perception of "otaku." I didn't want to be part of a group stereotyped as a bunch of creepy loners. This image of the antisocial otaku is so dominant that many of my Japanese acquaintances connect the term's origin to the kanji for household (taku 宅) because "otaku stay at home and avoid social interactions."

But this commonly believed etymology is dead wrong. In reality, social interaction is the heart of otaku culture. Lawrence Eng writes,

Contrary to the stereotypical image of the otaku as socially isolated, anime fan communities are highly social and networked, relying on combinations of online and offline connections… Otaku knowledge requires immersion in not only information and media but also in ongoing social exchange about topics of interest.

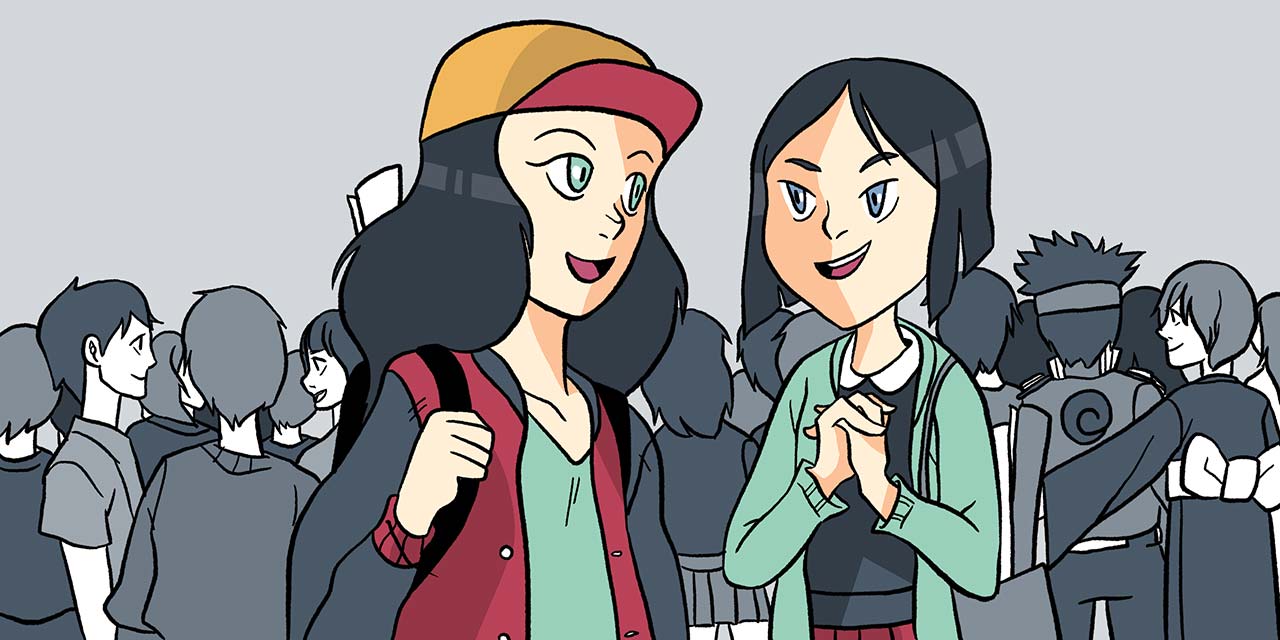

Otaku gather as informal groups of friends, formal college clubs, on message boards, at game centers, and giant conventions. As Patrick Galbraith puts it, "Connections emerge, and spaces of interaction arise as people share the moment – as in matsuri (festivals)"

For me anime has proved the ultimate ice-breaker. Once coworkers discover we share an interest in the same anime, inhibitions fall and conversations flow. Perhaps I am more otaku than I originally thought.

As a subculture fueled by gathering and sharing information, otaku don't shun interaction. They depend on it. And sharing information is valued as much as acquiring it.

As a subculture fueled by gathering and sharing information, otaku don't shun interaction. They depend on it. And sharing information is valued as much as acquiring it. In monokomi ものコミ or "thing-communication," series' details, collectibles, and breaking news earn respect among fans.

Otaku appreciate unofficial fan activity as much as, if not more than, official productions. Cosplayers don't just meet to show off. They exchange costume tips. Teams form to create doujinshi and sell them at conventions. Internet communities share custom art, home-made figures, and fan fiction.

The ultimate embodiment of these efforts gathers twice a year at "Comic Market" or Comiket, a convention which deals in fan-made products. The enormous event draws 35,000 creative "circles" and over half a million people. At least the convention-going element of my original otaku definition proved true.

The subculture gained enough momentum to transform the city districts of Ikebukuro and Akihabara into so-called "otaku mecca," complete with social fixtures like maid cafes, game centers, live conventions, and events that contradict the antisocial image.

What Makes Otaku Exceptional Nerds

Now that I've dispelled some of the negative stereotype surrounding Japanese nerd culture, we need to figure out what it means to be otaku, the true meaning behind otaku. Obviously, being social and sharing information isn't all there is to it.

But don't worry. I've narrowed "what being otaku means" down to a single word: possession.

By this, I don't necessarily mean physical possession, like figures from someone's favorite anime. What I mean is otaku take ownership of their beloved series by examining every detail. Then they take it a step beyond by creating costumes, fan fiction, music videos, figures, art, and even new series based on their favorite universes.

According to Tamaki Saitou, "Being an otaku means being able to play around a little with the works you like; if you sanctify and worship them too much, you've fallen to the level of a mere maniac or fan."

In my quest to discover my own otaku-ness, I had to ask myself, how sacred do I hold my favorite anime? Do I have what it takes to "possess" my favorite series? In other words, am I a real otaku or just a run-of-the-mill maniac?

Otaku vs. Maniacs

Like otaku, "maniac" or maniakku マニアック dedicate themselves to a specific interest. Both subcultures focus on obsession and collecting. This has made the two words interchangeable in most people's minds. But small nuances differentiate the two.

- マニアック

- enthusiast

Maniac revel as spectators in their obsession. They value tangible objects that have intrinsic value. Camera maniac, for example, research and covet cutting-edge cameras, or rare antique ones. Even ordinary people can see value in various cameras. As Tamaki Saitou puts it:

Maniac have a concrete materiality. By concrete materiality I mean simply that one can pick them up in one's hands and that they can be measured. Generally speaking, maniacs compete with each other in terms of how effectively their hobbies translate into materiality.

Otaku's wide array of interests incorporate both the tangible (comics, figures, and apparel) and intangible (facts and knowledge). Both have value which may not be apparent non-otaku, particularly in the case of fan made works.

Remix + Exchange = Possession

Maniac take a passive role enjoying their obsessions. But otaku are contributors and participants. They value homemade, derivative products such as fan-made comics, stories, figures, and art. These are things maniac and ordinary people would not understand. Tamaki Saitou writes,

- 世界観(せかいかん)

- world view

(Otaku) know that the objects of their attachment have no material reality, that their vast knowledge has no use for other people in the world and that this useless knowledge may even… be viewed with contempt and suspicion.

Otaku take possession of what they love and make it their own. They take a fictional series' official universe sekaikan 世界観 (worldview) into account. But the author's vision is not absolute. And this possession is the result of remixing the source material and contributing it to the community. Tamaki Saitou continues,

(Otaku are) not just fans, but connoisseurs, critics, and authors themselves. This blurring of the distinction between producer and consumer is another characteristic of the otaku.

Otaku take official series canon into account. But the author's vision is not absolute. Remix and customization are the otaku subculture's soul.

My simplified image of otaku as hardcore fans missed the mark. I didn't know creativity built the unique foundation of otaku-dom. When I became an anime fan in the mid-nineties, the lack of merchandise inspired me to make custom t-shirts and patches for my favorite series. Unknowingly, I partook in the most otaku-centric activity there is!

Japan dubbed this phenomenon nijisousaku 二次創作 or secondary production. This stands in stark contrast to the primary production of the actual creators and rights owners.

- 二次創作(にじそうさく)

- derivative work

Cosplay, fan fiction, fan games, music, doujinshi, and other creative activities empower otaku. They foster participation and ownership of the beloved series. Japan's plethora of hobby specific magazines cover plastic model kits, illustration, customized game systems, and cosplay. The importance of grassroots creativity proves otaku function as an "open source remix culture," a term coined by Fenchy Lunning.

How Japan Encourages Children to Become Otaku

It's no wonder derivative works play such a vital role in the otaku realm. Japanese culture encourages this type of ownership in young children. Japanese children don't just spectate, they take part. In Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive Lawrence Lessig writes,

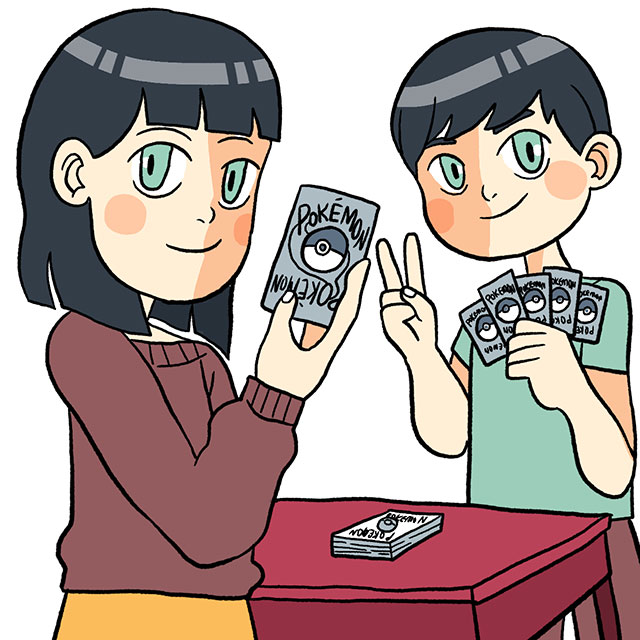

Japanese media have really been at the forefront of pushing recombinant and user-driven content starting with very young children. If you consider things like Pokemon and Yu-Gi-Oh! as examples of these kinds of more fannish forms of media engagement, the base of it is very broad in Japan.

He goes on to say that while American culture teaches children to buy a product and enjoy it as is, Japanese culture encourages children to create with their products.

This is broken down into three stages:

Stage 1: Creativity Encouraged

In the first stage creativity is encouraged in a preset universe with a rigid structure. For example, Pokemon doesn't just offer a cartoon or game, but an immersive universe to explore, study, and participate in. Lawrence Lessig elaborates:

Pokemon is something you do, not just something you read or watch or consume… The child assembles what they know about Pokemon from various media with the result that each child knows something his or her friends do not and thus has a chance to share this expertise with others… Every person has a personalized set of Pokemon.

Children choose which pocket monsters to catch, keep and, evolve. These choices encourage responsibility and ownership, which leads to simple remixing during the early stages of childhood development.

Stage 2: Creativity Practiced

In the second stage, creativity is practiced. Children use experiences from the encouragement stage to create more freely. Instead of respecting the barriers of a pre-established universe, children add their own elements or create unique universes of their own.

As a teacher in Japan I have seen this creativity in the classroom first hand. Kindergarten girls draw their own heroines. High school students try their hands at manga. Creativity is the norm rather than the exception in Japan. I wonder if the creativity I exhibited as a kid encouraged my current otaku tendencies?

Stage 3: Creativity Realized

In the third stage, creativity is realized when creators' production, organization, and distribution near a professional level. In fact, the former hobbyists might turn pro, making their hobby a lifelong career.

Yudetamago, two friends that began drawing manga together as children, is a remarkable example of creativity realized. The duo began winning awards for their amateur manga in junior high school. Their breakthrough series, Kinnikuman, remixed Ultraman and pro-wrestling before evolving into a unique comedy-action series. The success of Kinnikuman enabled the duo to become professional manga artists at a young age.

Derivative Works

While some otaku fans never reach the professional level, most are content to continue creating as a hobby. Instead of creating their own worlds, narratives, or characters, they celebrate official series and share their creations with fans able to appreciate them.

Fueled by ingenuity, fans have blurred the line between official releases and derivative works. Cosplay and cosplay-photography evolved hand-in-hand, giving birth to amazing costumes and photos that outshine their professional counterparts. Customized figures molded in fan-made resin-kits can look better than official merchandise. Anime Music Videos (AMV) implement professional editing techniques to produce musical tributes that get anime fans' blood pumping.

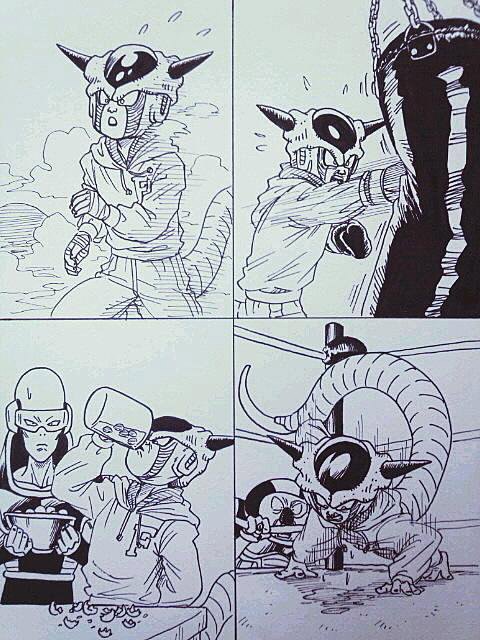

Fan fiction is used to fill plot holes or illustrate details neglected by series creators. For example, twitter user @dragongarowLEE created a training montage (shown above) that was alluded to, but not shown in the movie Dragon Ball Z: Resurrection F.

Some derivative works make up for disappointments in the official narrative. Many dissatisfied Neon Genesis Evangelion fans re-imagined their own endings for the series.

Otaku treat derivative works as seriously as the "real" thing, blending the official and unofficial. Many of today's industry giants got their start mimicking or parodying their favorite series.

Other times derivative works place characters in new situations or stories. These projects scratch a fan's personal itch, like the desire to see characters cast in gender bender, boys love, or hentai (erotic) situations. The famous studio Clamp took this approach, putting their own spin on the popular series Captain Tsubasa and Saint Seiya.

Culture critic Hiroki Azuma has said, "If we fail to consider the derivative works of amateurs in favor of only the commercially manufactured, projects and products, we will be unable to grasp the trends of otaku culture."

Unlike otaku, Western fans tend to worship the official narrative, known as canon or Gospel. They celebrate a deep knowledge of the series. Few fans embrace the unofficial which are brushed off as counterfeit, lesser quality, or illegal. As a result, Western culture tends to dismiss the importance of unofficial efforts.

Otaku treat derivative works as seriously as the "real" thing, blending the official and unofficial. Many of today's industry giants got their feet wet mimicking, homaging, or parodying their favorite series. If it weren't for sections dividing them, I wouldn't be able to differentiate between "real" and "fan" works at Japan's used book shops. Yet, my growing enjoyment of fan comics, fan games, and fan films adds to the growing weight of my otaku-ness.

Pre-Internet Pioneers

By today's standards otaku don't appear all that special. Nerd culture has overtaken the mainstream in the West.

As a kid, I was uncool for collecting comic books. But superhero movies like The Avengers and Deadpool are cool enough to net huge, diverse audiences. Playing video games was once considered childish. But today it's a legitimate sport with competitions, sponsorships, and huge cash prizes. And YouTube channels are producing nerdy fan films and parodies left and right.

It seems otaku possession culture has finally gained a foothold in the West. But it took a lot longer than it did in Japan.

High speed internet allows for instant communication, access to information, and circulation of media. Affordable production equipment has made fan projects easier. Crowdfunding and social media has enabled Western fans to connect, finally reaching otaku levels of creativity and participation. Without these technological advances, Western nerds might still be lagging behind Japan's otaku in terms of organization and remix culture.

This is partly the fault of Western media rights holders. Even if Western fans had attempted otaku-style remix and exchange, strict copyright enforcement would have squashed it. As a result, even hardcore fans failed to reach otaku status, forced against their will to remain mere maniac, enjoying the official as spectators.

Otaku Possession culture has finally gained a foothold in the west, but it took longer than it did in Japan. Western nerds are finally reaching otaku levels of creativity and remix.

But even if copyright barriers were absent, would the Western nerd movement have reached the same swell as Japan's otaku? Until recently, "canon" or official world-view reigned in Western nerd-dom. Fans anticipated official releases, argued about universe details, and lashed out when creators' visions didn't meet expectations. Collectors prized official comics, figures, promotional goods, and other official products. Though this is slowly changing, there still seems to be a preference for the "legitimate" over the "counterfeit."

But in Japan, otaku possession culture bloomed decades ago using grassroots distribution techniques like mailing lists, fanzines, fan circles, and conventions that overcame the era's technological limitations. Otaku respected the unofficial, the non-canon, and the independent from the very start. Western fans gained physical possession through merchandising and prided themselves on knowledge of the official universe. But their creative possession paled in comparison to Japan's otaku.

Otaku's Mainstream Redemption

"Otaku" has come a long way. The underground greeting gained unfortunate recognition thanks to the "Otaku Murderer." But the shunned subculture worked hard to shed its stigma and has finally gained something akin to mainstream acceptance. Otaku culture launched a lucrative industry that's spread across the globe. Worldwide appreciation and respect has given anime an air of legitimacy and otaku culture has won respect from surprising sources.

Comical, heartfelt spins on the otaku motif, like the popular drama Densha Otoko, depicts Japanese nerds as kind and hardworking people. It moved away from critical animalization and allowed outsiders to empathize with the shunned and misunderstood subculture.

More recently, the Japanese government harnessed otaku culture as a form of international "soft power." The government's official Cool Japan program encourages the spread of anime fandom abroad, hoping to aid Japan's international popularity and promote tourism.

Moreover, official government programs are helping anime culture flourish in Japan. In an attempt to encourage domestic anime production, the Japanese government created the Young Animator Training Project, funding animation ventures by up and coming artists.

With so much support from the government and the general public, it's easy for me to feel comfortable calling myself otaku. After all, it may get me a chance to meet the Prime Minister!

Say It Loud, "I'm Otaku and Proud"

Though I don't go for cat ears, have never attended a convention, and love basking in sunlight, the next time someone asks "Are you otaku?" I will answer, "Yes!" without hesitation.

I made orange Dragon Ball shirts with fabric paint long before they appeared in stores. I sought out dingy basements in Chinatown to purchase grainy Ghibli VHS tapes. My life has been enriched by a wealth of otaku activities. I and many other Western nerds were otaku before we knew the term existed. We just lacked the wherewithal to gather and create to the same degree our Japanese counterparts have been for decades.

But judging from the mainstream popularity of nerd culture and increasing prevalence of fan participation, the global otaku trend is growing. Nerds the world over are beginning to remix and possess their fandom like otaku. Whether it's superhero comics or fantasy football, there's certainly something you're a nerd about. And if you "possess" your nerdery through remix or exchange, then welcome to the long tradition of otaku-dom.

I'm certainly an otaku. Are you?